Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar5.2025007

Abstract

The objective of this study is to evaluate the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients, the indications, technique and results of diagnostic hysteroscopy at the Nabil Choucair health center Daker, Senegal.

Material and Methods

This is a prospective, descriptive, cross-sectional study carried out at the Nabil Choucair health center in Dakar, Senegal, from July 01, 2023 until August 01, 2024, a period of 13 months. The study concerns 155 women who underwent a diagnostic hysteroscopy with exhaustive sampling. Hysteroscopy was performed on the ninth day of the menstrual cycle in cycling women and at any time in postmenopausal women. Hysteroscopy was performed by vaginoscopy. Parameters studied included socio-demographic characteristics, indications, technique and results. Data entry and analysis were performed using Epi info 7 software.

Results

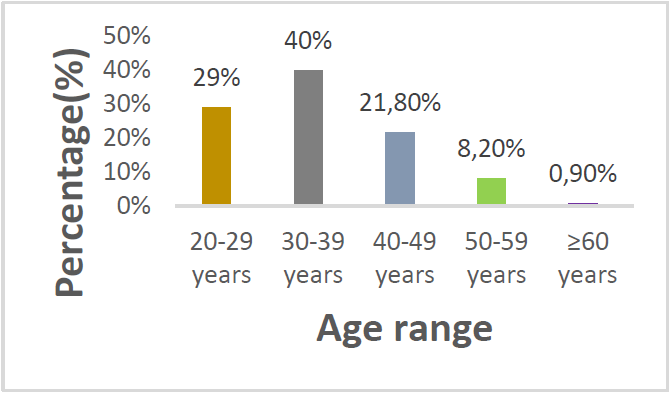

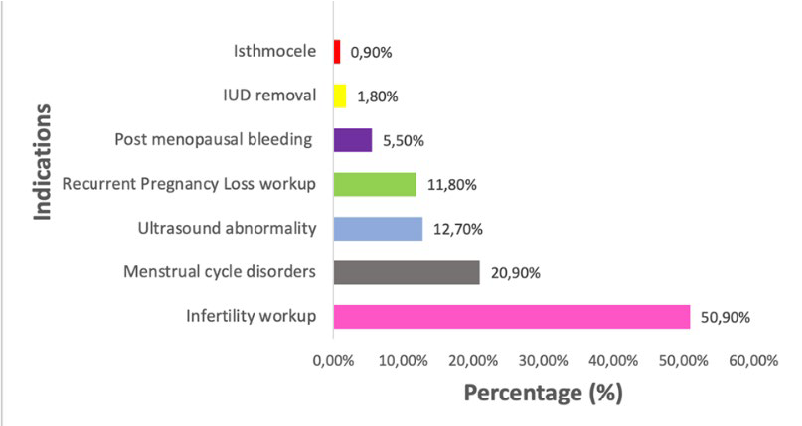

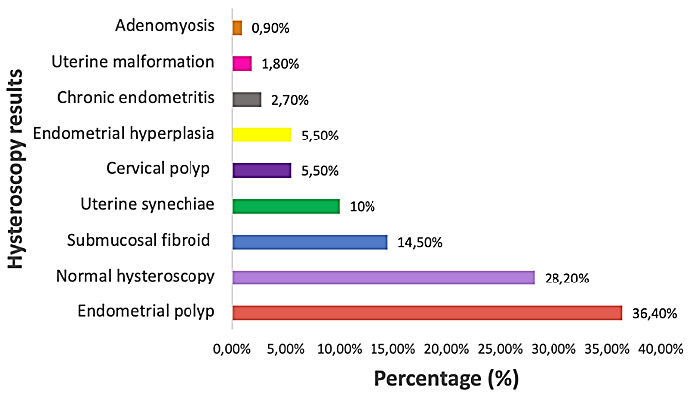

During the study period, 155 diagnostic hysteroscopies were performed. The mean age of the women was 35 years, varying between 20 and 73 years. In our series, the 30-39 age group (40%) was the most represented, followed by the 20-29 age group (29.1%). The women were married (94.5%) and lived mainly in the Dakar region (97.2%). Indications were dominated by infertility (50.9%). Other indications were cycle disorders (20.9%), endo cavitary pathologies on ultrasound (12.7%), recurrent abortion (11.8%), postmenopausal abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) (5.5%). Hysteroscopy was abnormal in 71.8% of cases. Lesions found were endometrial polyps (36.4%), submucosal myomas (14.5%) and uterine synechiae (10%). The most frequently reported complication was pain, ranging from simple discomfort to intense pain. Pain was reported by 17 patients (15%), with a visual analogue scale (VAS) score of 5.

Conclusion

Hysteroscopy is an essential examination in the management of endocavitary gynaecological pathologies and the exploration of infertility. Its ease of use in conjunction with vaginoscopy should make it an extension of the gynecological examination in certain situations.

Introduction

Modern hysteroscopy is the fruit of almost 200 years of evolution, first enabling to see inside the uterine cavity and then to perform surgical procedures previously performed by laparotomy (1). The first endoscope enabling us to see inside the uterine cavity by reflecting external light was developed by the German Bozzini between 1804 and 1807. The first hysteroscopic examination on a live patient was performed by Pantaleoni in 1869 on a patient presenting with postmenopausal bleeding (2). Subsequent modifications have led to modern endoscopes. Hysteroscopy is an examination involving direct visualization of the interior of the uterine cavity using an optic passed through the cervical canal. It can be performed for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. It is an examination that can be considered on an outpatient basis. Improved endoscopes with smaller outer diameter (now thinner, in the order of 15 French – 4,9 mm) and the use of gentle distension media such as saline under atmospheric pressure make this procedure simple and painless in the vast majority of cases, enabling it to be widely used in outpatient clinics, with excellent patient acceptability (3). In addition, it offers the advantage of direct visualization of the uterine cavity and endometrium, enabling biopsies of suspicious anomalies to be taken during the procedure (4, 5). The technique is also useful for diagnosing abnormalities of the cervico-isthmic canal (false tract, recesses, niches, synechiae), endometrial hypertrophy or atrophy, endometrial congestion suggestive of endometritis, vascular dystrophy and small intra-cavitary lesions (polyps, submucosal myomas, synechiae). Hence its importance in the management of infertility and the etiological investigation of recurrent abortions. Thanks to advances in hysteroscopic instrumentation, the physician is now able not only to assess abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), but also to plan treatment, which can considerably reduce the number of unnecessary major surgical interventions (6,7). Nevertheless, like any invasive procedure, hysteroscopy can give rise to complications, but these are rare and in the vast majority of cases minor (7). Hysteroscopy has therefore become an indispensable complementary examination in gynecology, and the gold standard for diagnosing endo-uterine anomalies for some. In Senegal, numerous studies have been carried out to investigate the practice of hysteroscopy in our context. according to Diop et al of 168 hysteroscopies performed in 2019 at the CHU Aristide le Dantec, 72.47% of cases were found to have endo uterine lesions (8). In view of this impact on the diagnosis of gynecological pathologies; we were interested in the practice of diagnostic hysteroscopy at the Nabil Choucair health center (CSNC) in the Dakar health region during the period from July 2023 to August 2024.

Material and Methods

1.1 Type and duration of study

A prospective study was conducted over a 13-month period from July 2023 to August 2024.

1.2 Study population

The study population consisted essentially of women who consulted for diagnostic hysteroscopy during the period from July 2023 to August 2024.

1.2.1 Inclusion criteria

Included in the study were all patients who underwent diagnostic hysteroscopy during the study period.

1.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Patients whose files were incomplete and those whom we were unable to contact were not included in the study.

1.3 Data collection

Data were collected using a survey form containing the following parameters: civil status, history, indications, results, complications and technique used (see appendix). Data were obtained from a register completed by the physician.

1.4 Studied variables

The variables studied were socio-demographic characteristics, patient history, indications, technique, results and complications.

1.5 Data entry and analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed using Epi info 7 software. It comprised two parts: descriptive analysis and analytical analysis. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for quantitative variables, and headcounts and percentages for qualitative variables. The analytical study consisted of an analysis of the different outcomes and complications according to history and indication. The Chi 2 test was used to compare proportions. The difference was statistically significant when the p-value was strictly less than 0,05.

1.6 Technique

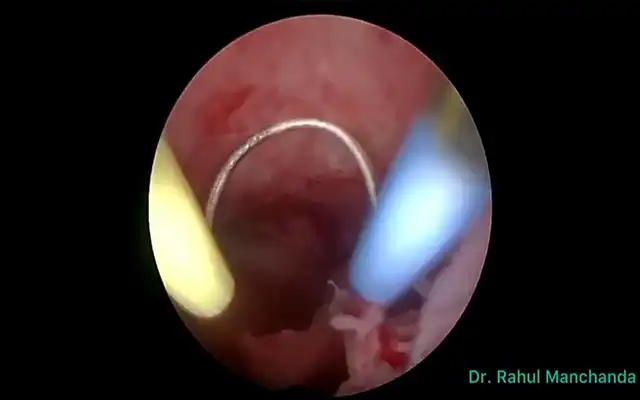

Vaginoscopic hysteroscopy is a “non-contact” technique considered to be the standard for ambulatory hysteroscopy. It is an atraumatic approach which considerably reduces the pain stimulus generated by the cervix and vagina through the use of the Pozzi’s tenaculum forceps and speculum, as well as the manipulation of the instrument. The hysteroscope used is the one with rigid optics.

In the practice at the Centre de Santé Nabil Choucair in Dakar, vaginoscopy is the preferred method, and involves several stages.

- First stage: vaginal examination, to assess vaginal trophicity, the posterior vaginal cul-de-sac and, above all, the orientation of the uterine cervix.

- Second step: the hysteroscope is gently introduced with the dominant hand, while the non-dominant hand opens the posterior vaginal fork. The hysteroscope is oriented towards the posterior vaginal cul-de-sac.

- Third step: the hysteroscope is withdrawn 1 to 2 cm from the posterior vaginal cul-de-sac and straightened in front of the external orifice of the uterine cervix, which is easy to see when diagnostic hysteroscopy is performed for unexplained vaginal bleeding, as a bloody discharge is noted, or for the visualization of cervical mucus.

- Fourth step: characterized by crossing of the internal os. At this point, the patient feels a sudden pain due to innervation of the endocervix, the glandular crypts of the endocervix can be observed.

- Fifth step: this consists of moving from the cervical-isthmic canal towards the uterine fundus, appreciating the ease and difficulty of advancing into the uterine cavity.

- Sixth step: this is an essential stage, and marks the start of the hysteroscopic exploration, with assessment of the uterine fundus, the anterior and posterior surfaces of the uterine cavity, the right and left lateral walls of the uterus, and the right and left tubal ostia. The endometrium and cervicoisthmic anatomy can also be assessed.

- Seventh step: the hysteroscope is withdrawn a few centimetres for a panoramic view of the uterine cavity.

- Eighth step: retrograde view of the uterine cavity, tubal ostia, cervico-isthmian canal, internal and external cervical orifices.

- Ninth step: the results are explained to the patient, and a report is drawn up. During the sixth step, a biopsy may be performed in the case of isolated endometrial pathology or pathology associated with endometrial pathology.

Results

2.1 Frequency

During this period, 3914 patients underwent a gynaecological consultation at the Nabil Choucair health center. Of these, 155 had undergone diagnostic hysteroscopy. This represents a proportion of 3.96% hysteroscopies.

2.2 Socio-demographic characteristics

2.2.1 Age

The mean age of the patients was 35 years, with extremes from 20 and 73 years. The 30-39 age group (40%) was the most represented, followed by the 20-29 age group (29.1%). Patients aged 30-39 accounted for 40% of cases (figure 1).

2.2.2 Marital status

In our series, all patients (94.5%) were married, singles (4.5%) and widows (1%).

2.2.3 Background

2.2.3.1 Gynecological and obstetrical history

- Sexual activity. In our study, 89.1% of patients were sexually active and 10.9% were menopausal.

- Menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle was regular in 60.9% (n=67) of women.

The mean length of the menstrual period was 6 days, with extremes of 3 and 20 days. - Contraception

In our study, only 15.5% of patients were on contraception. The pill was the main contraceptive method used (33.3%). - Gestation

The average number of pregnancies was two, with extremes from 0 to 8. Nulligravidae represented the majority (36.4%, n=40), followed by paucigravida (23.6%, n=26). 20 % were primigravidae and multigravida - Parity

The mean parity was 1 ± 1.8, with extremes from 0 to 8 deliveries. The median was one delivery. Nulliparous women accounted for 49.1% (n=54), followed by primiparous women 20% (n=22). - Abortions

Concerning abortions, 34.5% (n=39) had a history of abortion, of which 30.9% (n=34) had had at least two.

2.2.3.2 Medical and surgical history

- Medical history

In this series, 14 patients (12.7%) had a medical history, arterial hypertension being the main one (50%, n=7). - Surgical history

In this series, 17.3% (n=19) had a surgical history, and caesarean section was the main medical history reported (52.4%, n=11).

2.3 Indications for hysteroscopy

Infertility work-up 50.9% (n=56) was the main indication for hysteroscopy. Abortion assessment accounted for 11.8% of indications, (Fig 2).

2.4 Results of hysteroscopy

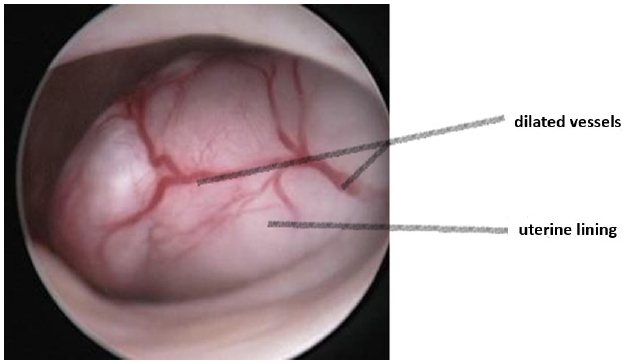

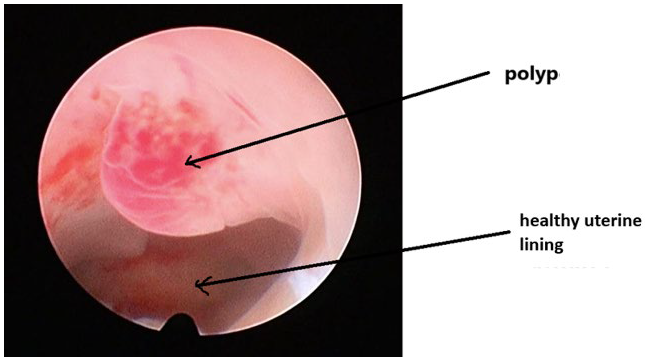

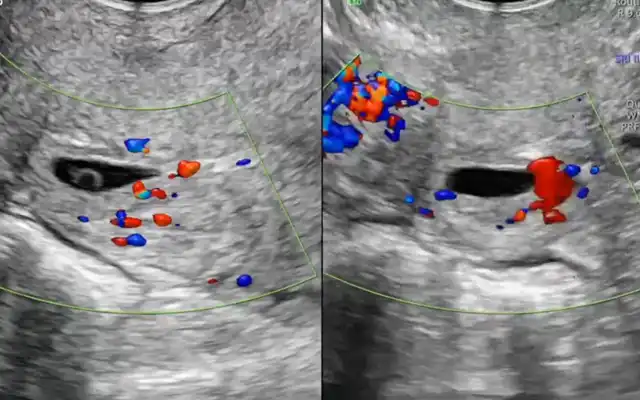

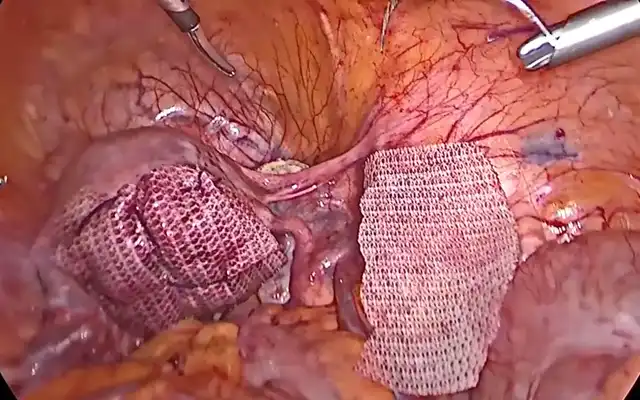

Hysteroscopic findings were abnormal in 71.8% of cases, and were mainly dominated by the presence of polyps (36.4%) and myoma characteristics (Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 5). It should also be noted that cervical preparation with Misoprostol was required in 3 patients (1.93%) prior to hysteroscopy, due to cervical spasm.

Hysteroscopy findings myoma (14.50%) as shown in figure 3.

The hysteroscopic findings were mainly dominated by the presence of polyps (36.4%) a specimen is shown in figure 5.

2.4.1 Associated gestures during hysteroscopy Associated procedures were performed on six patients (4.5%), with two biopsy curettages and two IUD removals.

2.4.2 Complications of hysteroscopy

Complications were noted in 19 (n=21) patients. Pain was the main complication (15.4%). Pain according to the mean VAS score was five, with extremes between 3 and 9.

Discussion

3.1 Frequency

During the study period, 155 patients underwent diagnostic hysteroscopy out of a total of 3914 gynaecological consultations, representing 3.96%. This frequency is relatively low compared with European series (9,10). This can be explained by the fact that hysteroscopy is not widely available in our region, due to the high cost for the population.

3.2 Socio-demographic characteristics

Our study concerned 155 patients who had undergone diagnostic hysteroscopy. Hysteroscopy was performed in both sexually active and postmenopausal women. However, the percentage of sexually active women was much higher, 89.1% versus 10.9%. The mean age in our series was 35, with extremes from 20 and 73. Patients aged between 30 and 39 accounted for the majority of cases (40%). Our results are similar to those reported by Diop 2021, Balde et al 2018 and Diallo et al 2013 (8,10, 11). In Kinshasa, DRC, according to the results of Nzau-Ngoma et al, the mean age was 35.7 years (12).

3.3 Gynaecological and obstetrical history

The average pregnancy rate was two, with extremes between one and eight. Nulligravidae accounted for 36.4% of cases. The average parity was one, with extremes between zero and eight. Nulliparous women accounted for almost half of all patients, 49.1% (n=54).

3.4 Indications for hysteroscopy

More than half the women (50.9%, n=56) in this study had undergone a hysteroscopy for infertility, and the majority (69.1%) were aged between 20 and 40 years. According to several authors, it is important to explore the uterine cavity when assessing infertility, as numerous intra-uterine lesions can be found. Hysteroscopy is currently one of the most reliable means for the correct exploration of the uterine cavity (13,14,15,16). A retrospective study of 145 patients included in an in vitro fertilization program, in whom hysteroscopy had been systematically performed, showed 45% pathology. These lesions consisted mainly of endometritis, polyps and myomas, and dystrophic mucosa (17). Cycle disorders accounted for 26.3% of cases, and AUB for 43.5% (n=10) in women of childbearing age. Hysteroscopy is a useful diagnostic tool in the investigation of patients aged 40 and under with AUB, since it enables the detection of an intra-cavity lesion that is most often unidentifiable at endometrial biopsy. It therefore seems preferable to recommend diagnostic hysteroscopy rather than endometrial biopsy in the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in these women (18). Metrorrhagia was also found in postmenopausal women (5.5%, n=6). In 2019, at the CHU Le Dantec, menometrorrhagia constituted the majority of indications with 56.5% all ages combined (8). In cases of AUB in postmenopausal women, hysteroscopy can identify intrauterine lesions (19, 20). In cases of recurrent AUB or endometrial thickness greater than 4 mm in post-menopausal women, further uterine investigations (hysteroscopy and histology) are recommended (21). The endometrial pathology most frequently found during hysteroscopy in women aged between 45 and 80 is the endometrial polyp (22). The search for the aetiology of recurrent abortions accounted for 11.8% of indications. Uterine anomaly is one of the main causes of recurrent miscarriage, in addition to age, genetics, phospholipid antibody syndrome and sperm quality. Studies have shown that congenital uterine anomalies occur in 4.3% of the general population of fertile women and in 12.6% of patients with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity is therefore recommended in these patients (23).

Hysteroscopy was performed following an abnormal ultrasound. Hysteroscopy was used to identify the various types of lesions. The main advantages of diagnostic hysteroscopy are direct visualization of the cervical canal and uterine cavity, and the possibility of targeted biopsies and even minor surgery (24). In 0.9% (n=1) of cases, it was performed for postoperative uterine control in a woman with a symptomatic isthmocele following Caesarean Section (CS).

3.5 Hysteroscopic technique

At the Nabil Choucair health center, the technique used is vaginoscopy. This is the technique recommended by several authors to minimize complications (16-17). In a study comparing vaginoscopy with the standard technique, the success rates of the techniques were comparable (95.5% vs. 96.3%), but the median time required to perform vaginoscopy (135 seconds) was significantly shorter than for standard hysteroscopy (190 seconds). The median pain score was also significantly lower than for standard hysteroscopy (18). In this series hysteroscopy was performed without anesthesia, during the first phase of the cycle. The use of Misoprostol for cervical preparation was not systematic. Vaginal Misoprostol reduces cervical resistance in women undergoing hysteroscopy and facilitates the procedure, with only mild side effects (19). No antibiotic prophylaxis was used. Saline was used as a distension medium. Hysteroscopy was performed on an outpatient basis, and no hospitalization was observed. These different techniques were recommended to reduce the frequency of per- and post-hysteroscopic complications (9,19,20). A prospective study of 530 in-office diagnostic mini-hysteroscopies performed on infertile patients demonstrated that the use of an atraumatic insertion technique, an aqueous distension medium and the new generation of mini-hysteroscopes, enabled hysteroscopy to be performed without any form of anaesthesia and with high patient compliance. The high number of abnormal findings (28.5%), the absence of complications and the low failure rate (2.3%) indicate that in-office diagnostic mini-hysteroscopy should be a first-line diagnostic procedure (21).

The failure rate was 2.72% in this series. Hysteroscopy could not be performed in three women due to cervical spasm. In two of these women, cervical preparation with Misoprostol was performed, enabling successful hysteroscopy. High success rates of over 90% are consistently reported for such outpatient procedures in the various reviews. The most common failure rates reported in the literature are due to pain and the inability to visualize the uterine cavity correctly due to cervical stenosis (22). Vasovagal episodes have also been reported (23). A retrospective observation of 512 hysteroscopies from January 2016 to November 2018 had shown an office hysteroscopy failure rate of around 12% (n=16). Severe pain due to cervical stenosis, previous surgery on the uterus, menopause and marked retroflexion of the uterus were the main reasons for failure reported (22). Furthermore, operator experience appears to be a key factor both for accurate endometrial assessment and for reducing failure rates (24, 25).

3.6 Hysteroscopic findings

Hysteroscopy was abnormal in 71.8% of cases. The abnormalities found were mainly endometrial polyps, submucosal myomas, uterine synechiae and endometrial hypertrophy. The percentage of endometrial polyps was 36.4%. And this finding concerned both menopausal and sexually active women. Submucosal myomas accounted for 14.5% of cases. These are the two most common hysteroscopic anomalies in cases of infertility (26). Uterine synechiae were found in 10% of women. Five women had a history of curettage and two had a history of pelvic surgery. This confirms that uterine synechiae are most often of post-traumatic origin, occurring in 90% of cases in the post-partum or post-abortum period (19). According to Schenker and Margalioth, among the 1856 cases of Asherman syndrome found in a review of the literature, pregnancy was the dominant predisposing factor found in 90.8%, with 66.7% of synechiae occurring after post-abortal curettage, 21.5% after post-partum curettage, and 2% after CS (27). Hysteroscopy is by far the best tool for diagnosing intrauterine adhesions and assessing their severity in real time (28).

In 5.5% of cases, there was endometrial congestion. At CHU Le Dantec endometrial hypertrophy was the most common anomaly, with 93 cases (60.1%) (8).

In this series, only 1.8% (n=2) of women had a uterine malformation, most frequently a septate uterus. In addition to a septate uterus, one of these women had a bicornuate uterus. Diagnostic hysteroscopy plays an essential role in the diagnosis and management of congenital anomalies of the genital tract. Combined with clinical examination and imaging, it is a valuable tool for evaluating and correcting these anomalies (29).

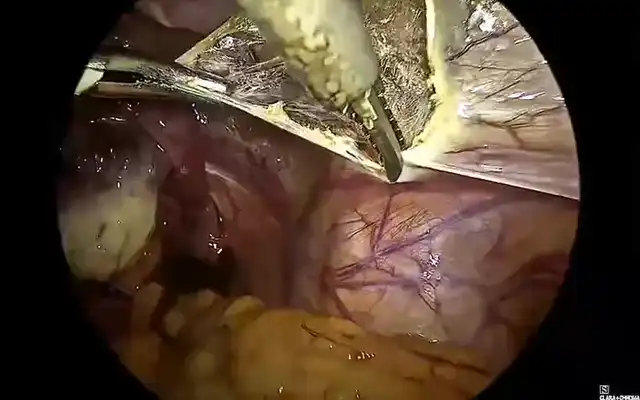

3.7. Related procedures during hysteroscopy

Following diagnostic hysteroscopy, procedures were performed on 4.5% (n=5) of patients. Two successful intrauterine device (IUD) removals were performed. It was confirmed that hysteroscopy can indeed be used to remove IUDs that are difficult to remove. It is an effective method, generally well tolerated, with low morbidity (30). Out of 12 women who consulted for IUD wire migration, the IUD was found by hysteroscopy in the uterine cavity in 10 cases and successfully removed. Vaginoscopy can also be used to remove intra-vaginal foreign bodies more safely (31).

Uterine biopsy was performed in two women with suspicious lesions, including endometrial hypertrophy and adenomyosis. Hysteroscopic endometrial biopsy is often recommended. It enables targeted sampling when there is a localized abnormality (32). A polypectomy was performed in a 26-year-old nulligravida woman who had consulted for AUB. Hysteroscopy revealed an endometrial polyp, which was successfully resected.

3.8 Complications

Vaginoscopy is a speculum- and tenaculum-free hysteroscopic technique offering the greatest patient comfort and the lowest pain levels (29). The approach used to insert the scope, as well as the diameter of the hysteroscope and distension of the uterine cavity, are of extreme importance in minimizing patient discomfort during an ambulatory examination. One of the major problems with endoscopes is passage through the cervical os (28).

In our series, complications were rare and in the majority of cases minor. In 17 cases the patients reported pain. The majority were moderate, of the discomfort type, with an average VAS of five. Only one case of severe pain was reported in a 52-year-old G8P2 patient with a history of post-abortal curettage who had consulted us for post-menopausal AUB, and in whom the hysteroscopy was in favour of uterine synechia.

Conclusion

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is undoubtedly an essential complementary examination in gynaecology. Today, it is recognized as the gold standard in endo-uterine exploration. Its diagnostic value lies in its ability to directly explore the uterine cavity.