Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.vid25006

Abstract

Deep endometriosis located in the middle and posterior compartments involves the parametrium, which contains nerve structures, uterine vessels, and the ureter. Therefore, a preoperative evaluation and endometriosis mapping are imperative. The parametrectomy and discoid resection technique for deep endometriosis, performed using the reverse technique in a 37- year-old patient without reproductive desire, allows for a systematic approach with the preservation of critical structures. The use of fluorescence minimizes postoperative complications and provides Good surgical outcomes.

For many years, surgical techniques have been the subject of study in cases of deep infiltrative endometriosis affecting the medial and posterior compartments, due to the various structures involved and the dysfunctions that may arise after excisional procedures. As a result, endometriosis surgery has evolved toward the preservation and identification of critical structures.

Learning Objective

Implement surgical strategies in parametrectomy for deep endometriosis, focusing on neurovascular preservation, identification of critical structures, and prevention of postoperative complications.

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma, or the resulting fibrosis, infiltrating the peritoneum by at least five mm (1). Among the most frequent locations associated with debilitating pain, pelvic organ dysfunction, and reduced quality of life is the dorsolateral parametrium, due to its anatomical relationship with the neuro-pelvis (2). The lateral parametrium can be defined as an area connective tissue composed of areolar tissue that surrounds the visceral branches of the hypogastric vessels as they travel toward the uterus and vagina (3).

The lower hypogastric plexus is formed by a multitude of splanchnic nerves originating from the sacral plexus, the sympathetic trunk, and the lower hypogastric nerve. During the evolution of endometriosis surgery, numerous postoperative neurogenic disorders were described, which led to the shift toward preserving nerve structures to date (4). Endometriosis affecting the parametrium can extrinsically affect the ureter, being clinically asymptomatic in up 30% of patients, or it may be associated with non-specific symptoms. However, in a minority of cases, progressive upper urinary tract obstruction leads to asymptomatic renal function loss due to progressive extrinsic compression of the ureteral wall by the endometrial tissue (5).

The parametria can be considered the “neurological electrical unit” of the pelvic viscera. The formation of the pelvic plexus arises from sacral roots S2-S3-S4. Through the union of the pelvic splanchnic nerves and the hypogastric nerves. The preservation of the fibers can prevent pelvic floor dysfunctions (6).

In relation to the anatomical classification of parametrectomy, deep parametrectomy type 1 (DP1) is located medial to the presacral fascia and cranial to the middle rectal artery. Deep parametrectomy type 2 (DP2) is caudal to the middle rectal artery, and deep parametrectomy type 3 (DP3) is lateral to the hypogastric fascia (7).

Patient and Methods

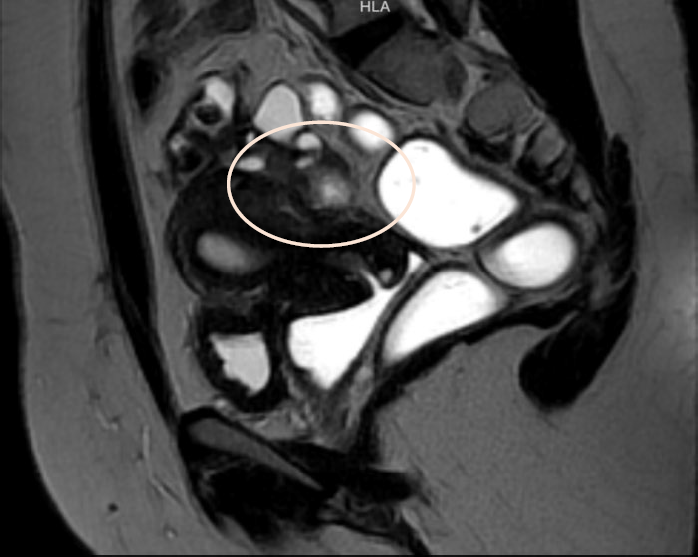

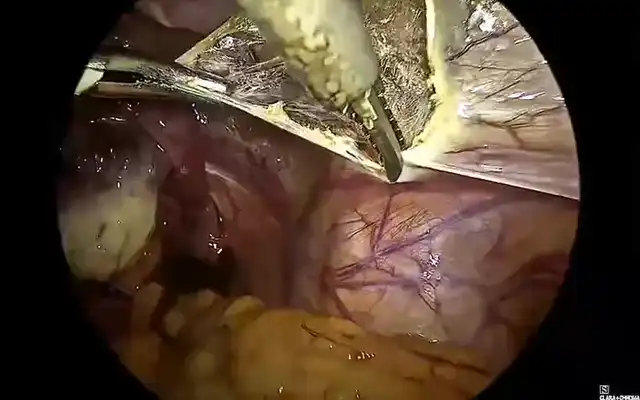

The case of 37-years-old patient, Gravida 1, Para1, with a clinical history of chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and dyschezia is presented. Endometriosis mapping was performed using MRI to assess lesions in the lateral and posterior compartments due to the clinical symptoms. Significant findings included: Diffuse posterior uterine adenomyosis, a 3,4 cm adenomyoma, a 38×27 mm retro cervical nodule with extension to the uterine torus and posterior vaginal fornix retraction. An endometriotic lesion of 26 mm on the anterior wall of the rectum with involvement of the muscular layer. #ENZIAN v2021: P0, 0 ½, T 3/3, A1, B2/3, C2 FA (Fig 1-2) The patient gave consent for scientific publication of this video, contributing to the scientific literature and surgical advancement.

Surgical Technique

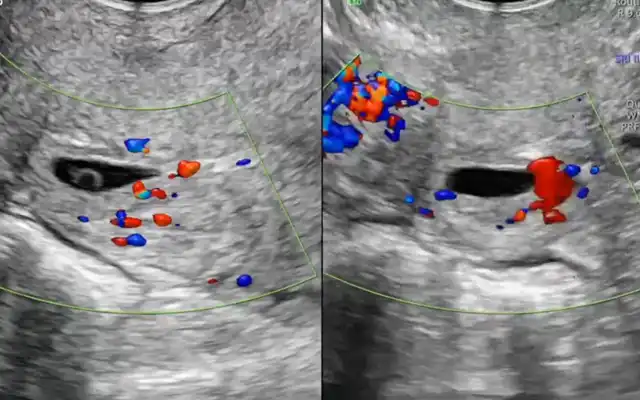

Under general anesthesia, the patient is placed in the Lloyd-Davies position. Cystoscopy is performed with the insertion of an open-end ureteral catheter, through which fluorescent solution is injected. A trans umbilical incision is made for the insertion of a 10 mm main trocar, and pneumoperitoneum is established at 12 mmHg. Accessory five mm trocars are placed in the right iliac fossa and the left suprapubic area. A 30 degrees laparoscope is used to perform a panoramic inspection of the abdominopelvic cavity.

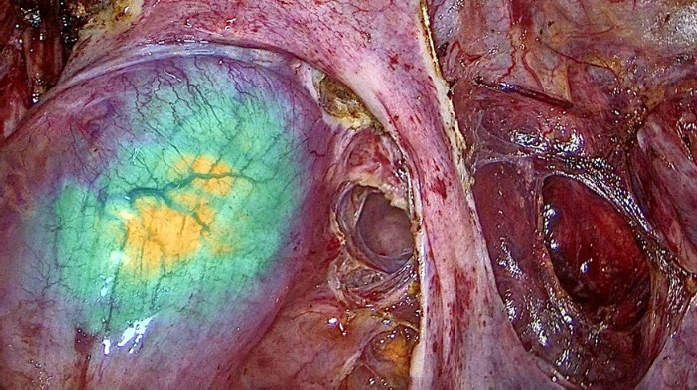

Findings: The uterus is adherent to the anterior rectal wall via the mesorectum. The ovaries are adherent to the posterior uterine wall, with the presence of the “kissing ovaries” sign. The right ureter is adherent to an ipsilateral parametrial implant. Both ureters are visualized using the fluorescence filter system.

Using ultrasonic and bipolar energy, pelvic peritonectomy is performed from lateral to medial, following the reverse technique. This includes bilateral transection of the round ligaments, and dissection of the vesico-uterine space as well as the bilateral medial para-vesical spaces. The anterior leaf of the broad ligament is dissected to identify the two Latzko spaces, followed by visualization of the origin of the two uterine arteries, the obliterated umbilical artery, and the superior vesical vessels. The mesorectum adherent to the posterior uterine wall is dissected until the rectovaginal septum is reached, free of endometriotic involvement. The Okabayashi space is dissected bilaterally to preserve the neural structures of the inferior hypogastric plexus, until the left margin of the rectovaginal septum is identified. The right parametrium is dissected, revealing an extensive periureteral endometriotic nodule measuring approximately two- three cm.

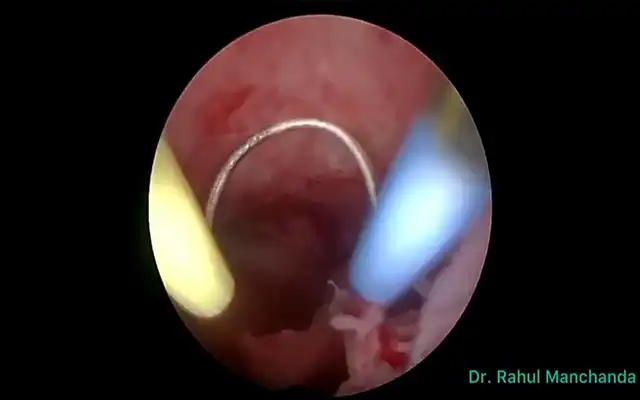

This is excised using ultrasonic energy, followed by ureterolysis. The dissection of the mesorectum continues, and an anterior colpotomy is performed until the rectovaginal septum is exposed. The rectovaginal nodule is dissected, and the posterior colpotomy is completed.

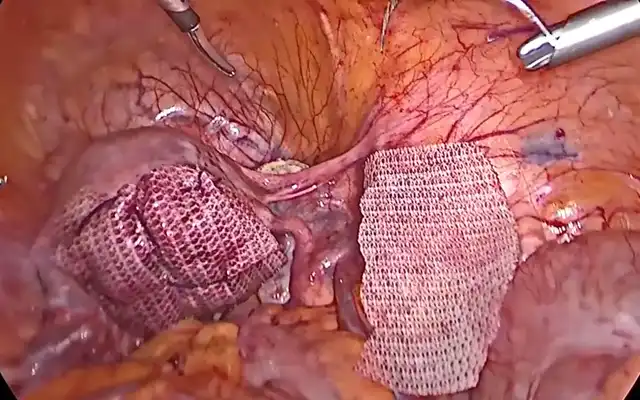

The surgical specimen is extracted vaginally. The rectal nodule is identified with a suture marker placed 12 cm from the anal verge. A circumferential mesorectal dissection is performed, and a discoid resection is carried out using a 29 mm circular stapler. Reinforcement sutures are placed on the intestinal serosa with 3-0 Monocryl, and intestinal perfusion is confirmed via fluorescence. A pneumatic leak test confirms the absence of leakage. Finally, vaginal cuff closure is performed with 1 Vicryl™ suture.

The total surgical time for parametrectomy and discoid resection for deep endometriosis in the medial and posterior compartments, combined with hysterectomy using the reverse technique, was 99 minutes. During the procedure, advanced technology was employed to identify and preserve structures such as the ureters, which were compromised by bilateral parametrial nodules.

Discussion

The importance of preserving neural structures has evolved over the years in the surgical management of deep endometriosis, as numerous cases of pelvic floor dysfunction have been reported in postoperative patients with endometriosis involving the lateral and posterior compartments. For this reason, nerve preservation may help prevent bladder and rectal dysfunction and reduce the risk of diminished vaginal lubrification and arousal in women. Several studies have evaluated the causes of pelvic floor dysfunction after surgery for endometriosis. Consequently, surgical approaches to lesions in the lateral and posterior compartments have become a critical point of investigation. Although endometriosis is a benign disease, it affects multiple structures and organs. Therefore, modern surgical approaches must aim to preserve critical structures such as nerves and/or vessels of adjacent organs to avoid future complications (12).

The main difference between conventional endometriosis surgery and the reverse technique lies in the approach to the lesion: the reverse technique begins dissection from healthy peripheral tissue toward the lesion, allowing the surgical team better visualization of key neurovascular structures. Given the pathophysiology of the disease – with its strong neurovascular affinity and tendency to infiltrate surrounding structures, along with anatomical distortion and fibrotic inflammatory changes – this approach has shown reduced intraoperative risks and improved postoperative recovery (8,9,10,11).

The total surgical time for parametrectomy and discoid resection for deep endometriosis in the medial and posterior compartments, combined with hysterectomy using the reverse technique, was 99 minutes. During the procedure, advanced technology was employed to identify and preserve structures such as the ureters, which were compromised by bilateral parametrial nodules (11,13).

Minimally invasive surgery today offers greater safety, especially with the use of fluorescence to identify vital structures and/or confirm adequate vascular perfusion in cases of intestinal involvement requiring segmental resection (14). A thorough preoperative evaluation with endometriosis mapping is essential, as it provides the pelvic surgeon with a comprehensive view of the affected sites and helps define the surgical strategy – such as the use of fluorescence to identify critical structures and verify intraoperative vascular flow. In addition, the use of a rectal mobilizer with fluorescence helps delineate the exact location of the rectal nodule with greater precision Fig 3. (14). The reverse surgical technique enhances surgical access, and its systematic steps make it a reproducible method.

Conclusion

Endometriosis surgery with parametrectomy and identification of critical points using technological support minimizes postoperative complications. This likely standardised, step-by-step technique standardises the procedure and indirectly reduces surgical times, thus favouring the procedure and ultimately leading to better outcomes for patients.