Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.2025021

Abstract

Heterotopic pregnancy is defined as the simultaneous presence of an intrauterine pregnancy and an ectopic pregnancy in the same patient, independent of the location of the ectopic pregnancy. This is a rare and often unrecognized pathology that poses a diagnostic problem and can be life-threatening if not diagnosed in time. The case reported is of a heterotopic pregnancy, seldom described in the literature; an eight-week evolving triplet pregnancy including a ruptured tubal pregnancy and a twin intrauterine pregnancy. Management consisted of laparoscopic surgery, with salpingectomy to eliminate the ruptured tubal pregnancy while preserving the intrauterine twin pregnancy. The post-operative course was marked one week later by the death of one of the intrauterine twins. The pregnancy was closely monitored and an elective caesarean section performed at thirty-eight weeks enabled the birth of a healthy new-born who weighed 2500g.

Introduction

Heterotopic pregnancy (HP), also known as ditopic pregnancy or combined pregnancy, is defined by the simultaneous presence of an intrauterine gestational sac and an ectopic one. It is a combination of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) and an ectopic pregnancy (EP) in the same patient, independent of the location of the EP (1–3). This is a rare and often unrecognized pathology that poses diagnostic problems and can be life-threatening if not diagnosed in time (4–6). The case of a patient admitted to the University Hospital of Kinshasa, carrying an eight-week evolving triplet heterotopic pregnancy, including a ruptured tubal pregnancy and a twin intrauterine pregnancy, a sequence rarely described in the literature is reported.

Case

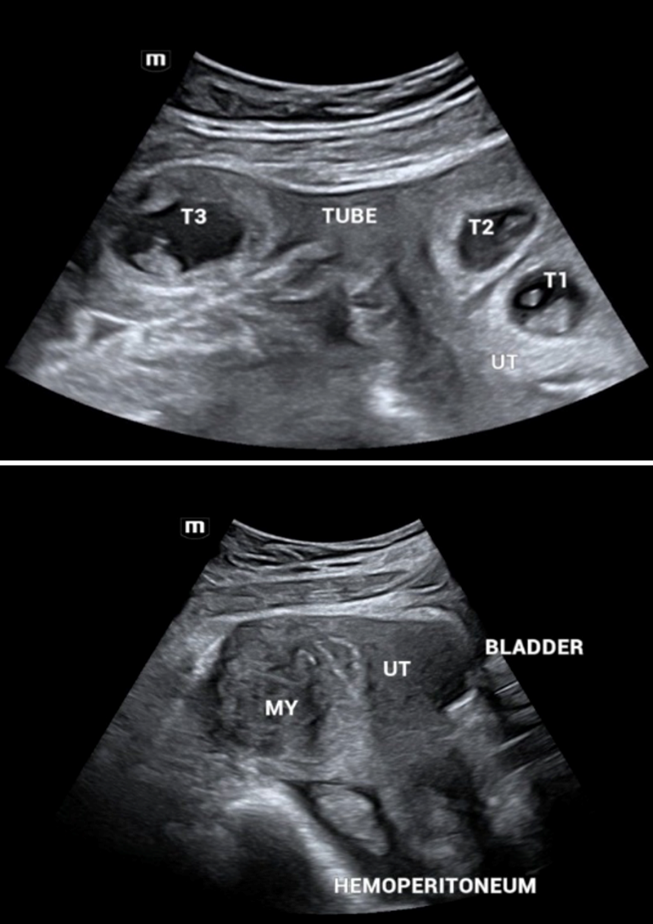

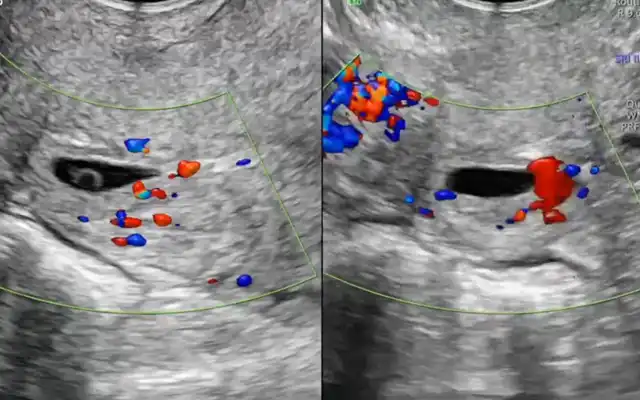

A 39-year-old female patient, married for two years, gravida two, nulliparous, consulted the Assossa Medical Polyclinic in December 2023 for fertility care. Her history included a miscarriage shortly after her wedding. The physical examination was unremarkable, and ultrasound showed fibroids: one antero fundal, type 3-5, measuring 41×30 mm, and two antero corporeal, type 4 and 3, measuring 25×19 mm and 18×12 mm respectively. Hysterosalpingography showed bilateral tubal permeability. She was also treated at the same clinic for an upper genital infection. In June 2024, she underwent ovulation induction with Clomiphene Citrate 50 mg daily from day two to six of the menstrual cycle, followed by progesterone twice a day 200 mg from day 17 to day 27 of the menstrual cycle. More than a month later, she went back to the hospital for a delay in her periods, and the pregnancy test was positive. A first ultrasound scan showed two intrauterine gestational sacs with no embryonic echoes. A second ultrasound two weeks later showed a heterotopic pregnancy with two intrauterine sacs and a sac in the right tube (Figure 1). The patient was transferred to the University Hospital of Kinshasa.

On admission, she was lucid, blood pressure was 125/80 mmHg, slightly tachycardic at 104 beats per minute, palpebral conjunctivae moderately coloured, abdomen not bloated, soft and depressible with tenderness to the right iliac fossa. On speculum examination, the cervix appeared healthy, the Douglas was not bulging, and on vaginal examination, the uterus was enlarged, with palpation of a 2 cm right adnexal mass, tender and soft. Ultrasound showed an evolving intrauterine twin pregnancy (with cardiac activity) of eight weeks, an evolving right ampullary pregnancy (with cardiac activity) with marginal trophoblastic detachment, moderate intra-abdominal bleeding ion and a large 53×49 mm type 5 postero fundal fibroid.

Management:

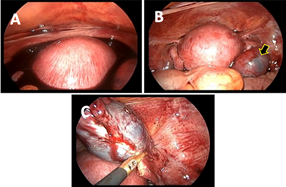

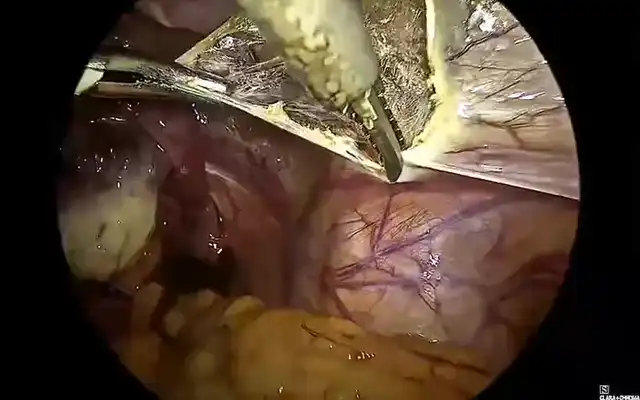

Prior to surgery, the patient was placed on an intramuscular progesterone injection combined with an antispasmodic infusion (phloroglucinol in glucose serum). The aim of treatment was to perform a salpingectomy while preserving the intrauterine twin pregnancy. Laparoscopic surgery was opted for, which revealed the following findings: a moderate hemoperitoneum with multiple blood clots, an enlarged gravid uterus, a ruptured right ampullary pregnancy no longer actively bleeding and normal left adnexa (Figure 2).

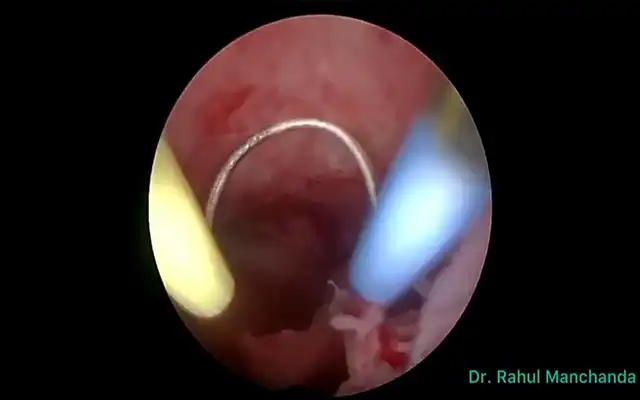

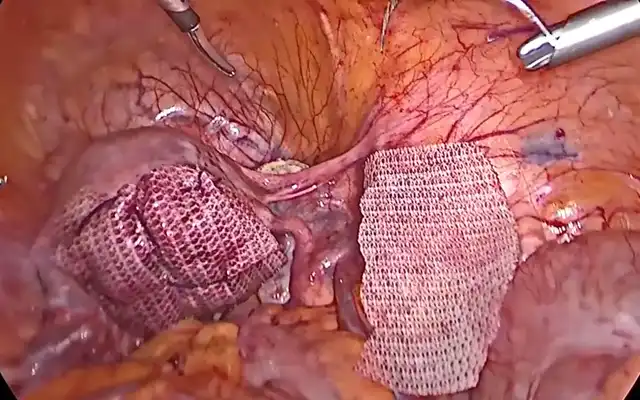

300 ml of hemoperitoneum were aspirated first and thereafter a total right salpingectomy was performed using bipolar shears with coagulation and cutting mode. An ultrasound performed immediately post- operatively showed an evolving intrauterine twin pregnancy, and the patient continued with her treatment consisting of progesterone twice a day 200 mg intravaginally and phloroglucinol three times 80 mg intrarectally. Another ultrasound scan performed a week after the operation showed the death of an intrauterine twin at nine weeks. Closer prenatal visits than the usual schedule were performed. At 38 weeks, the patient underwent an elective caesarean section which resulted in the extraction of a female healthy new-born weighing 2500 g with an APGAR of 9/9/10, a length of 48 cm, a head circumference of 33 cm and a chest circumference of 32 cm (Figure 3). Examination of the placenta revealed a single placenta with a para-central umbilical cord insertion without anomaly, suggesting the disappearance of the dead twin at nine weeks.

Discussion

Heterotopic pregnancy (HP) is a fairly rare pathology. The first case was discovered and described in 1761 by Joseph-Guichard Duverney (7) during the autopsy of a woman in the third month of pregnancy. In the literature, the reported frequency of heterotopic pregnancies in spontaneous cycles is 1/30.000 pregnancies. This frequency is multiplied by 60, even up to 300, when assisted reproduction techniques (ART) are used, i.e. 1/100 to 1/500 pregnancies (2,8,9). Today, its frequency is tending to increase with the development of ART (10). The resurgence of upper genital infections is also a major risk factor after ART (1,2,11). In terms of etiopathogenesis, several theories have been put forward. Ectopic implantation of one of the eggs may be due either to successive fertilizations of two oocytes by two spermatozoa, delayed in time, or to a difference in the migration speed of two simultaneously fertilized eggs. The inhibitory effect of progesterone secreted by the intrauterine implanted egg on tubal peristalsis may be the reason why the second egg stops progressing (1,12). The diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy should be made early (before rupture) to enable early management (13,14). However, the visualization of an intrauterine gestational sac very often does not motivate the sonographer to look for another location (4). A systematic review of the literature published in the UK showed that during the period 2005 to 2010, 33% of patients with heterotopic pregnancies had already had a previous ultrasound scan that had concluded to an intrauterine pregnancy (14). This was also the case for the patient presented in this study, whose heterotopic pregnancy was diagnosed at the second ultrasound scan. The most common ectopic location is tubal (15). Management of HP consists in eliminating the ectopic pregnancy and allowing the intrauterine pregnancy to progress (8). This may involve laparoscopic or laparotomic salpingectomy, ultrasound-guided transvaginal injection of potassium chloride, methotrexate or hyperosmolar glucose, even ultrasound-guided aspiration of the ectopic pregnancy (5,8,15-19). However, laparoscopy is currently the most recommended treatment, as it limits the risk of miscarriage, the prevalence of which after surgery remains around 6.2% (15). The disappearance of an intrauterine twin after salpingectomy, also known as Vanishing Twin Syndrome (VTS), is a complex and multifactorial condition. Although salpingectomy is intended to preserve the mother’s life by treating the ectopic pregnancy, in rare cases it can be followed by arrested development of the intrauterine twin. Potential mechanisms are: first intrinsic chromosomal or development anomalies of the intrauterine twin. This is the most frequently cited and most important mechanism in VTS, whether or not surgery is performed. The phenomenon of spontaneous reduction after vanishing of a twin is common in multiple pregnancies (20). The fading twin often carries chromosomal or genetic abnormalities that are incompatible with life. The resorption of this twin is a natural selection process. Salpingectomy, in this case, would not be the direct cause of the disappearance, but a concomitant event or stress factor that accelerates the detection of this underlying non-viability (21–23). The second mechanism is physiological stress. Ectopic pregnancy, particularly if it is symptomatic (pain, bleeding) or in the event of rupture, represents considerable physiological stress for the maternal body. Laparoscopic surgery, although minimally invasive, also adds to this stress. The presence of ectopic tissue, particularly in the event of tubal bleeding or rupture, triggers an inflammatory cascade. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1, TNF-alpha) and other mediators may be released (24,25). Although inflammation is crucial for implantation and maintenance of pregnancy, excessive or aberrant inflammation can be deleterious to early embryonic development and the uterine environment, increasing the risk of miscarriage (26). Surgical stress can also exacerbate this response especially if the uterus is manipulated during the operation (27,28). Finally, there is the stress of general anesthesia (29). The third mechanism is ischemia associated with local or systemic hypoxia: a ruptured ectopic pregnancy can lead to significant internal haemorrhage, which can cause systemic hypoperfusion in the mother. Although the uterus is a well-vascularized organ, even mild transient hypoxia or ischemia could compromise the viability of an already fragile intrauterine embryo (30,31). The last mechanism is the alteration in hormonal balance after salpingectomy. Although the intrauterine pregnancy is the main source of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) after a certain stage, ectopic pregnancy also contributes to the production of pregnancy hormones. Removal of this ectopic trophoblastic tissue can lead to hormonal readjustments. Salpingectomy removes a site of hCG production. Although the fall in hormone levels is generally minimal and the intrauterine twin is supposed to compensate, an already vulnerable intrauterine embryo could be sensitive to these fluctuations, however slight. A temporary reduction in hormonal stimulation could affect the endometrial environment and incipient placental function.

Conclusion

This case highlights the exceptional rarity and diagnostic challenges posed by heterotopic pregnancies. It provides valuable insights into the complexities of this rare condition. It reinforces the importance of considering heterotopic pregnancy in differential diagnoses, especially in patients with pain and pregnancy, and demonstrates that prompt surgical intervention can be life-saving while aiming for the best possible outcome for the intrauterine pregnancy. The subsequent close monitoring and successful delivery, despite the unfortunate early loss of one twin, highlight the resilience and adaptability required in managing such high-risk pregnancies.

References

Figure 1: Ultrasound findings: A shows three gestational sacs, two of which are intrauterine (UT) twins (T1, T2) and one in the right tube (T3). B shows a sagittal section of the pelvis. A posterofundal fibroid (MY) and an effusion in the Douglas suggesting hemoperitoneum were noted

Figure 2: A shows the hemato-peritoneum; B shows the pregnant uterus and the ruptured tubal pregnancy; C shows the salpingectomy

Figure 3: Caesarean section images