Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.vid25014

Abstract

Background: Deep infiltrating endometriosis with intestinal involvement occurs in up to one-third of patients and is often incompletely excised, with high symptom recurrence when managed in several steps. Standard laparoscopy frequently requires a mini-laparotomy for specimen retrieval, prolonging operative time and exposing patients to morbidity. Innovative combinations of en bloc resection and natural-orifice extraction aim to overcome these limitations by uniting radical clearance with a fully minimally invasive workflow.

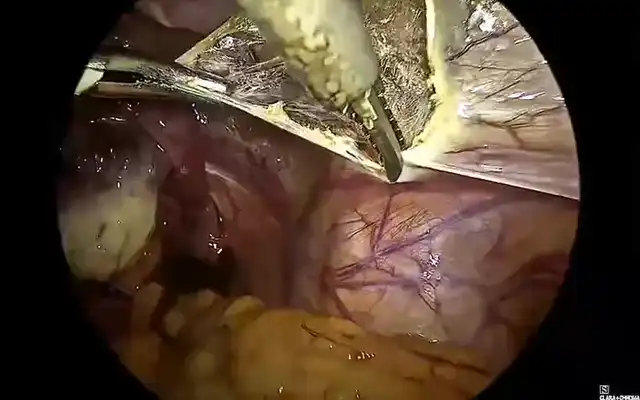

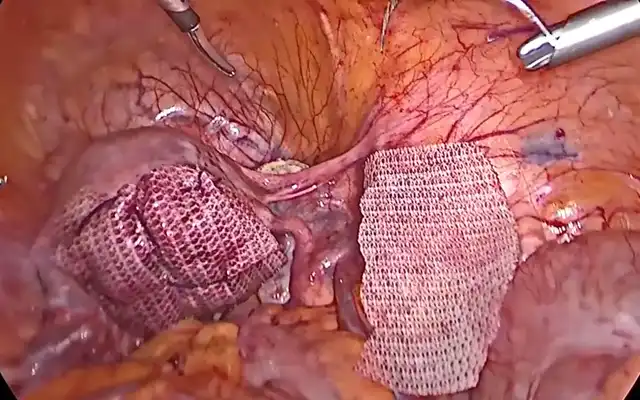

Methods: A multidisciplinary advanced-endoscopic approach applied to a 40-year-old woman with extensive DE staged P0 O2/2 T3/3 A3 B3/3 C3 FA on the #ENZIAN system is described. The operation began with an en bloc hysterectomy–segmental colorectal resection in which the uterus remained attached to the bowel nodule until colpotomy, the intact “pelvic block” was then delivered transvaginally via natural orifice specimen extraction.

Results: Removing the uterus and rectosigmoid as a single specimen prevented inadvertent luminal opening and ensured generous margins, eliminating visible residual disease. The natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) pathway avoided an accessory mini-laparotomy, shortening operative time, reducing abdominal wall trauma, and producing less post-operative pain and faster bowel recovery. No intraoperative complications occurred, and the patient was discharged uneventfully. Final pathology confirmed full-thickness bowel invasion with negative margins.

Conclusions: Combining en bloc hysterectomy-colorectal resection with transvaginal NOSE extraction is technically feasible and safe in complex intestinal DE. The strategy achieves comprehensive disease clearance while preserving the functional advantages of advanced endoscopic surgery, including quicker mobilization and patient comfort, and may lower perioperative morbidity and long-term recurrence risk.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, systemic and estrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder in which endometrial-like tissue implants are seen outside the uterus. It affects about 10 % of reproductive-age women worldwide, yet diagnosis typically lags 5–12 years after symptom onset (1). Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DE), one of the most aggressive variants, is defined by infiltration of more than 5 mm below the peritoneum and can involve organs such as the bladder, ureters, and frequently, the intestines. Intestinal involvement occurs in up to 37% of women with endometriosis, mainly affecting the rectosigmoid colon, and may present with nonspecific symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, dyschezia, or clinical pictures that mimic irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease, making diagnosis challenging (2,3). The management of intestinal DE represents both a clinical and surgical challenge due to its complex anatomy and the potential risk for complications such as bowel obstruction, perforation, or fistulas (4). The #Enzian classification is currently a fundamental tool for describing the extent and location of deep endometriosis, complementing the prior ASRM classification. This system assigns letters to anatomical compartments: A (vagina/rectovaginal septum), B (utero-sacral ligaments), and C (intestine), further subdividing intestinal involvement into C1, C2, and C3, according to depth and size. A C3 nodule refers to a lesion involving the rectosigmoid colon larger than 3 cm or compromising more than 50% of the bowel circumference (5). The surgical approach to intestinal nodules depends on both the depth and extent of the intestinal wall involvement and the size of the lesion. When the lesion is limited to the serosa or partially involves the muscular layer and is smaller than 3 cm, a shaving procedure or superficial excision can be performed, avoiding opening the bowel lumen. If the nodule is larger than 3 cm but does not compromise the entire circumference, or if infiltration affects the full thickness of the muscular layer and reaches the submucosa, a discoid resection is recommended. This technique removes a circular or “disc” segment of the affected intestinal wall while preserving the remaining circumference. However, when the nodule involves the mucosa or affects more than 50% of the bowel circumference, a segmental intestinal resection with anastomosis is necessary, as the risk of stenosis or perforation is higher with conservative treatment attempts (6,7). When deep infiltrating endometriosis involves multiple pelvic structures as a single anatomical block—such as the rectovaginal septum, uterus, ureters, and intestines—a surgical strategy known as en bloc resection is recommended. This technique consists of resecting all involved structures simultaneously in a single surgical procedure, respecting safety margins, with the goal of reducing recurrence risk and avoiding multiple surgeries (8). En bloc resection provides a more radical and safer approach when there is multifocal involvement, reducing the risk of residual disease dissemination and improving long-term functional outcomes (8). Additionally, the NOSE technique (Natural Orifice Specimen Extraction) has become increasingly used for the safe removal of surgical specimens. It allows the extracted tissue to be removed through natural orifices such as the rectum or vagina, avoiding additional abdominal incisions, reducing postoperative pain, minimizing wound complications, and improving cosmetic outcomes (4).

Material and methods

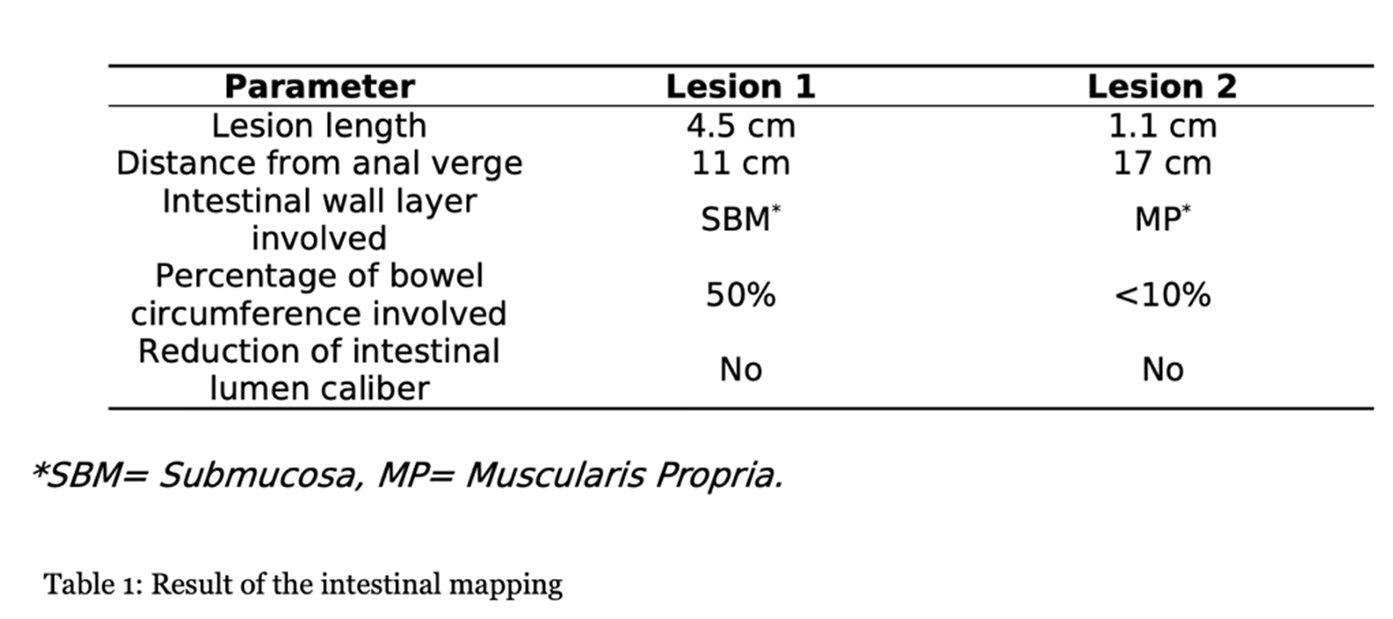

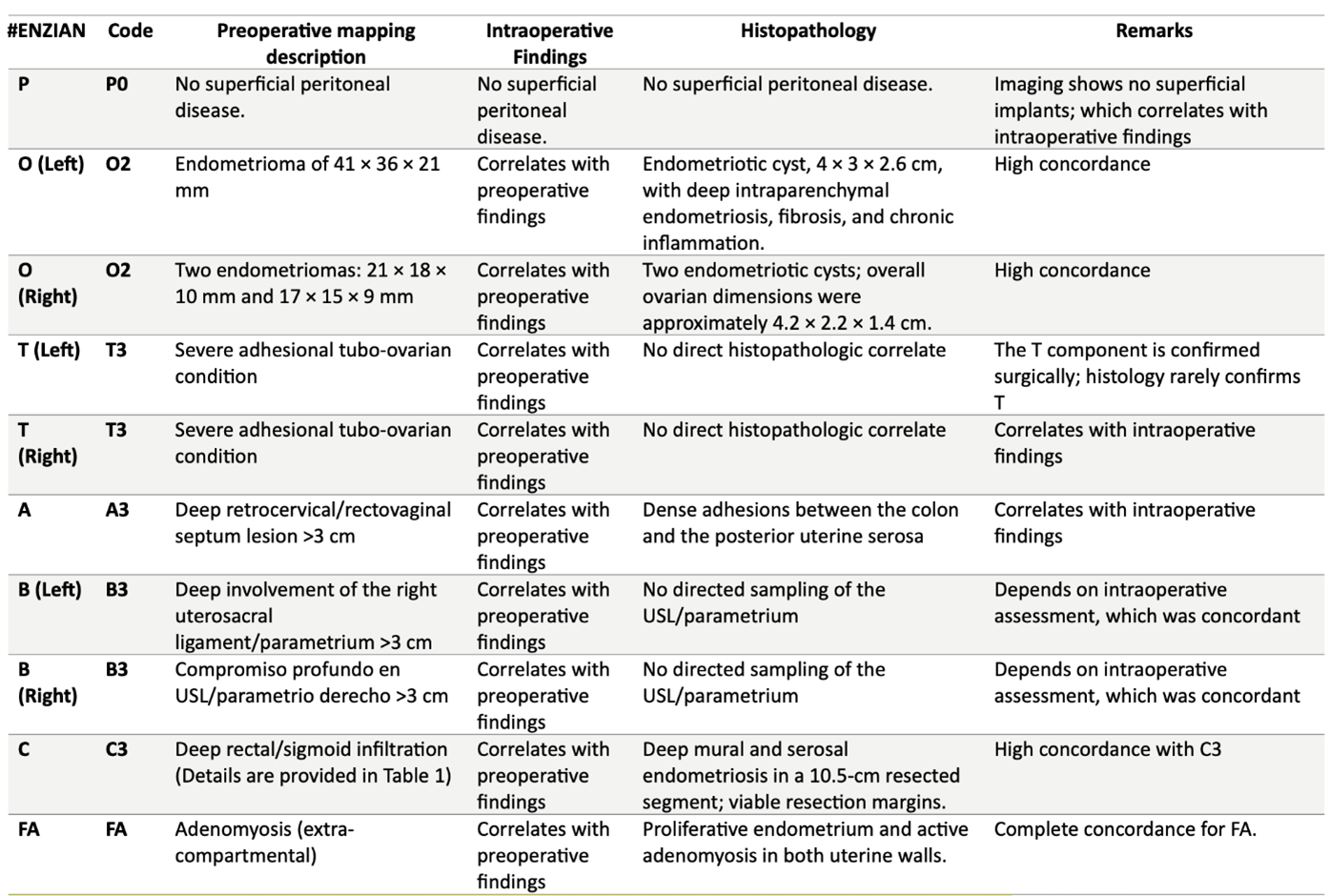

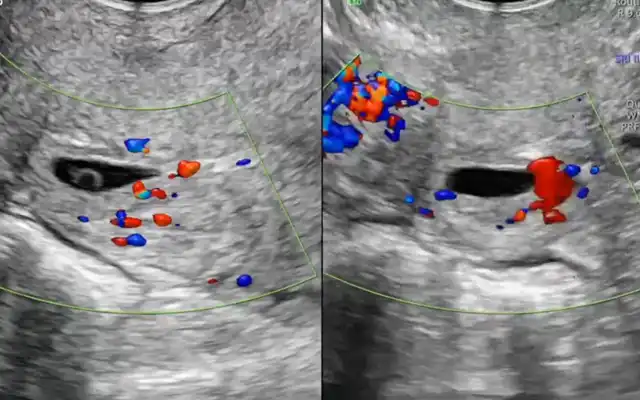

The case of a 40-year-old woman with clinically suspected deep endometriosis who underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using an endometriosis-dedicated protocol with intravaginal and intrarectal gel for compartment-based mapping is presented. The uterus appeared globular and heterogeneous, measuring 82 × 66 × 49 mm (calculated volume ≈ 140 cm³), findings consistent with concurrent adenomyosis. Disease distribution was coded with the 2021 #ENZIAN classification as P0 O2/2 T3/3 A3 B3/3 C3 FA, indicating bilateral stage-2 ovarian lesions, full thickness bilateral rectovaginal-septum infiltration, extensive uterosacral-parametrial involvement, deep anterior rectal-wall invasion, and focal adenomyosis. Ovarian assessment revealed two right-sided endometriomas measuring 21 × 18 × 10 mm and 17 × 15 × 9 mm, together with a single left-sided endometrioma of 41 × 36 × 21 mm. Bowel mapping demonstrated two nodular infiltrates situated 11 cm and 17 cm from the anal verge, involving 50 % and <10 % of the luminal circumference and reaching the submucosal and muscularis propria layers, respectively (Table 1). Clinically, the patient reported debilitating symptomatology characterized by severe dysmenorrhoea (visual-analogue-scale score 8–9/10), cyclic abdominal and pelvic pain that clearly intensified during menses, pronounced dyschezia, and intermittent haematochezia coinciding with the menstrual period, all of which markedly impaired her quality of life and work capacity. These imaging and clinical findings provided the anatomical and symptomatic framework for pre-operative planning and constitute the index case for the present study.

Results

The procedure lasted 110 minutes. Both ovaries were preserved, and the endometriomas were drained followed by complete capsule excision to minimize recurrence risk. The patient was closely monitored postoperatively with procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as surrogate markers for colorectal anastomotic integrity, which remained within normal limits. Food by mouth tolerance was achieved early, and she was discharged on the third postoperative day with adequate recovery and no immediate complications. At the one-month follow-up, she reported marked improvement of pelvic pain and bowel-related symptoms. Final pathology demonstrated proliferative endometrium and active adenomyosis in both uterine walls, the left ovary contained a 4 × 3 × 2.6 cm endometriotic cyst with intraparenchymal deep endometriosis, fibrosis, and chronic inflammation, the right ovary contained two endometriotic cysts, overall ovarian dimensions were approximately 4.2 × 2.2 × 1.4 cm; and the resected intestinal segment (total 10.5 cm) showed mural and serosal deep endometriosis with active bleeding, hemosiderophages-a, granulation tissue, and dense fibrotic adhesions firmly attaching the colonic wall to the posterior uterine serosa, with viable resection margins and nonspecific chronic inflammation. Overall, these findings showed a favourable correlation with the preoperative #ENZIAN mapping (P0 O2/2 T3/3 A3 B3/3 C3 FA): FA was fully corroborated by active adenomyosis; C3 aligned with deep mural/serosal intestinal infiltration across the resected segment with dense adhesions; the O component was partially confirmed (left-sided endometrioma with intraparenchymal deep endometriosis consistent with O2, without side-specific confirmation on the right), A3 (retro cervical/rectovaginal) and B3/3 (bilateral uterosacral/parametrial) were compatible with intraoperative findings but lacked directed sampling for definitive histology; and, as expected, T3/3 reflects a severe tubo-ovarian adhesion condition that typically lacks a direct histologic counterpart (Table 2).

Discussion

Deep infiltrating endometriosis that welds the rectosigmoid to the posterior uterus challenges surgeons to balance radical clearance with acceptable morbidity. The surgical findings support a sequential strategy: first, an en bloc hysterectomy-segmental colorectal resection in which the uterus remains completely attached to the bowel nodule until colpotomy allows the entire fibrotic complex to be delivered intact. This “single-specimen” manoeuvre secures wide margins, prevents inadvertent bowel opening during stapled resection, and maximizes removal of microscopic endometrial-like implants factors known to lower symptomatic recurrence. Second, routing the specimen through a natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) pathway preserves the minimally invasive character of laparoscopy by eliminating an accessory mini-laparotomy and any fascial extension. In the en bloc laparoscopic approach for uterine–rectosigmoid disease, transvaginal NOSE reduces abdominal wall trauma and pain, hastens bowel recovery, and enables one-piece delivery of the uterus–rectosigmoid complex, preserving orientation to assess depth and margins more faithfully; in our case, this translated into shorter operative time, negative margins, and an uncomplicated discharge. Beyond this case, comparative evidence in intestinal endometriosis shows that versus mini-laparotomy extraction, NOSE reduces length of stay and blood loss without increasing major complications or operative time; in fully laparoscopic resections it also shortens operative duration (9). A randomized controlled trial in rectal endometriosis reported similar functional and pain outcomes between NOSE and conventional laparoscopic resection, supporting that the principal advantage of NOSE is avoidance of an abdominal incision without a functional penalty (10). From a balanced perspective, a NOSE has route-specific limitations: these include colpotomy-related complications and pelvic infection, although uncommon, these are real. Pooled analyses place vaginal cuff dehiscence after minimally invasive hysterectomy at 0.7% (11). Comparative meta-analysis shows that, versus transabdominal extraction, transvaginal extraction lowers wound morbidity without increasing anastomotic complications when protective measures (specimen bag, irrigation) and careful selection are used (12). A large prospective study (n=4.565) also demonstrates a learning-curve effect: about 82% of conversions occurred within a surgeon’s first 50 cases, underscoring the need for structured training and proctoring (13). Finally, nulliparity is not an absolute contraindication; feasibility has been reported even in virginal patients when vaginal access is adequate and plans for conversion are in place (14). When combined, these techniques achieve comprehensive disease clearance while preserving the functional advantages of advanced endoscopic surgery, showing how multidisciplinary collaboration can modernize a historically morbid procedure. Extracting the intact en bloc specimen transvaginally also maintains the native orientation of the uterine–bowel complex, enabling the pathologist to evaluate depth and lateral spread of infiltration with greater fidelity; this more precise clinicopathologic correlation strengthens postoperative surveillance planning and guides subsequent therapeutic decisions. For reproducibility, this en bloc–NOSE approach should be embedded in a multidisciplinary program. Colorectal and gynecologic minimally invasive surgeons should jointly select cases, review imaging, and agree on the operative strategy (shaving, discoid, or segmental; en bloc when indicated). Standardized team briefings, shared ERAS pathways, joint morbidity-and-quality review, and cross-specialty proctoring during adoption support consistent outcomes.

Video

Conclusion

An operative approach that unites en bloc hysterectomy-colorectal resection with transvaginal NOSE extraction offers a compelling solution for the most complex forms of intestinal endometriosis. The en bloc step secures radical disease clearance and safeguards against intraoperative bowel injury, while NOSE preserves the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, collectively reducing operative time, perioperative morbidity, and the risk of long-term recurrence. These findings position the combined technique as a best practice option in high volume centres, prospective studies with extended follow-up are now warranted to confirm its durability and impact on quality of life.