Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.vid25016

Abstract

Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a rare but serious condition that can result in severe maternal and fetal complications and occurs when pregnancy implants on the uterine scar or in the niche after a previous caesarean scar (CS) (1). Due to its increasing incidence and lack of consensus regarding optimal treatment, the need for effective and standardized surgical strategies is growing. In this video article, a clinical case of CSP is presented and illustrated by a step- by-step laparoscopic technique for safe excision and correction of uterine defect.

Case report

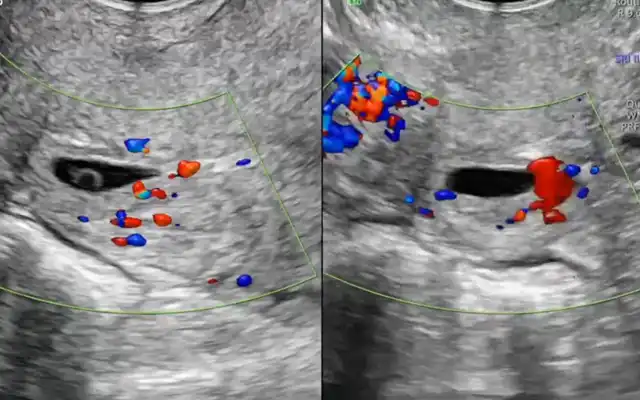

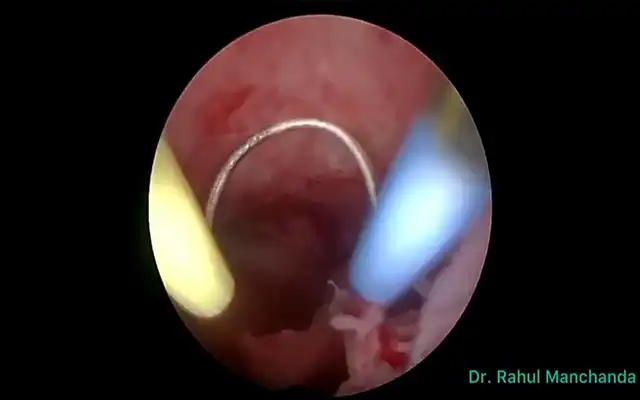

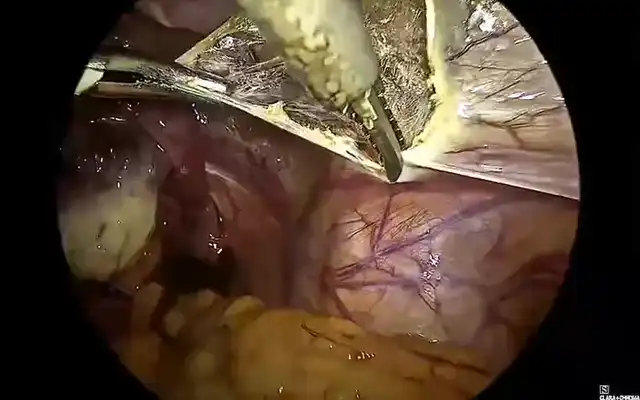

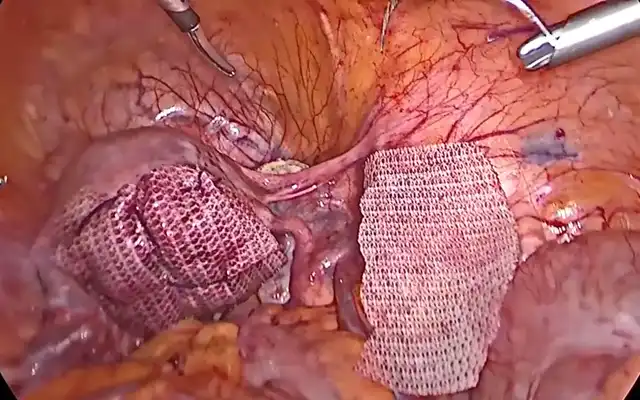

The case of a 42 -yr-old patient is presented, with 2 previous caesarean sections, gravida at 5 weeks and 5 days of gestation, asymptomatic. The early pregnancy ultrasound revealed a gestational sac measuring 15x14x6 mm, without embryonic structures, implanted in the Caesarean scar niche, without embryonic structures, and a residual myometrial thickness (RMT) of 2 mm. After informing the patient on the management options, she decided for a surgical management. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed, confirming the diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy in the isthmic region. Proceeding with a combined laparoscopic/hysteroscopic technique, the dissection of the vesicouterine space was performed, the isthmocele was opened and the pregnancy was removed together with the isthmocele pouch. Subsequently, with the guide of a foley catheter placed in the uterine cavity, the caesarean scar defect was repaired using a double-layer simple interrupted suture including the whole thickness of myometrium and endometrium. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged the following day. The patient is currently in the eighth month after surgery, with no reported complications.

Discussion

Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is defined as a pregnancy with implantation in, or in close contact with, the niche of a previous cesarean section scar (2). The true incidence of CSP remains unknown; however, it is estimated to occur in approximately 1:1.800 to 1:2.500 pregnancies in women with a history of Caesarean delivery (3,4). Its incidence has been rising, largely attributed to the increasing number of Caesarean deliveries and to advances in imaging techniques that allow earlier and more accurate diagnosis (5,6). The exact mechanism of CSP implantation is unclear, though proposed theories include low oxygen tension in the scar tissue and impaired healing of the Caesarean incision, both of which may predispose to abnormal trophoblastic invasion. It is believed that CSP is a precursor to, and shares a common histology with, placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) and that these constitute a continuum of the same disease (7). The clinical presentation of CSP is variable. Approximately one-third of patients are asymptomatic, with the diagnosis made incidentally during routine examinations, such as first- trimester ultrasound. The symptoms of CSP are generally nonspecific, the most frequent clinical finding is vaginal bleeding, pain may be present (1,5). Women with ruptured CSP may also present with massive hemorrhage and hemodynamic collapse (4). Early detection of CSP requires a high index of suspicion. Transvaginal ultrasound with color Doppler, ideally between 6–7 weeks of gestation, is the primary diagnostic tool (5). A low, anterior gestational sac in the scar site, close to the bladder and surrounded by Doppler flow, sometimes bulging outward, should raise concern for CSP (4,8) The following ultrasonographic criteria have been proposed for the diagnosis of CSP:

- empty uterine cavity and endocervix.

- sac or placenta embedded in the scar.

- triangular or rounded sac filling the scar niche.

- thin or absent myometrium.

- rich vascularity.

- embryonic structures with or without cardiac activity (7). Three-dimensional ultrasound and power Doppler may improve accuracy (4).

Differentiation from spontaneous miscarriage and cervical ectopic pregnancy is essential. CSP growth patterns include the endogenic type (Type I or “on the scar”), progressing toward the uterine cavity, which may rarely result in a viable pregnancy but with high risk of abnormal placentation and hemorrhage and the exogenic type (Type II or “in-the-niche”), invading deeply into the scar with a high risk of rupture and massive bleeding ((5,9,10). Recently, Ban et al. proposed a new five category clinical classification system based on anterior myometrium thickness at the scar and the diameter of the gestational sac with recommended surgical strategy, reaching high treatment success rates (97.5%) with minimal complications (6). Given the substantial risks associated with CSP, expectant management is rarely advised and pregnancy termination is generally recommended upon diagnosis (1,4,8). Treatment strategies include medical or surgical approaches, with the choice depending on severity of symptoms, CSP type, RMT, fertility desire, surgeon’s expertise, and institutional resources (5,6,9). Medical therapy involves the use of injectable medical agents or local pressure with devices such as balloon catheter. Medical management with methotrexate (MTX), either systemic or local, offers a non-invasive and low-cost option for fertility preservation but is associated with high failure and complication rates (1,11). Uterine artery embolization (UAE) and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) can be used in combination (1). Surgical management compared with medical therapy may be associated with higher success rates and includes hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, laparotomy, and gestational sac suction (8,11). It is indicated in hemodynamically unstable patients or after failed medical therapy, and offers the advantage of simultaneous scar repair, potentially reducing recurrence risk (1). The choice between hysteroscopy or laparoscopy depends on the CSP type. Hysteroscopy is more suitable for the endogenic CSP type while laparoscopy is indicated for exogenic types, although combined approach can be used. Hysteroscopy allows good visualization of the gestational sac and allows to assess the adequacy of any repair. Using a loop electrode without electricity, the products of conception are separated from the uterine wall (5). Laparoscopic excision is performed by first separating the bladder from the low uterine segment, followed by excising the uterine wall (wedge resection) and removing the pregnancy. The incision is then repaired. It is considered the most effective technique, with low complication rates and significant improvement in RMT, especially with multilayer closure (1,9). In either case, simultaneous scar repair can be performed and the choice of modality depends greatly on the RMT. Hysteroscopic resection is minimally invasive but limited with a RMT <2–3 mm, in which case laparoscopy is preferred (9). Laparoscopic repair under hysteroscopic guidance allows precise defect localization and complete resection, with reported postoperative increases in myometrial thickness and symptom relief (9,12,13). Vaginal approach involves excising the scar pregnancy through a transvaginal incision, followed by double-layer closure of the uterine defect. This technique is effective but requires surgical expertise and careful patient selection (1,13). Overall, early intervention is associated with better outcomes and combination treatments are very effective therapies to preserve fertility while minimizing complications (11,5). Despite multiple treatment modalities, no consensus exists on the optimal management strategy, highlighting the need for individualized care and further comparative studies (5,6). Subsequent pregnancies following CSP can happen with a risk for recurrent scar implantation, abnormal placentation, and uterine rupture (14). Patients who become pregnant after treatment of a CSP should be encouraged to have an early (5-7-week) first-trimester transvaginal scan to determine the location of the gestation (15).

Video

Conclusion

There is currently no consensus regarding the treatment of caesarean scar pregnancy, with various modalities described in the literature. Laparoscopic resection can be a safe and effective approach for managing these cases. This minimally invasive approach allows for precise resection while preserving uterine integrity and minimizing complications. The video is believed to help enhance comprehension of key anatomical and technical details that are crucial for successful outcomes.