Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar6.2025018

Abstract

Although uterus transplantation (UT) is a promising solution for women with absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI), it remains in the experimental phase with mixed outcomes across different studies, while alternative pathways to motherhood, such as surrogacy is accessible. To date, more than 90 UT procedures have been performed worldwide. However, various complications have been reported concerning the outcomes for donors, recipients, and neonates. These challenges highlight significant hurdles in the broader application of UT in clinical settings. At present, nearly all women with AUFI face a choice between involuntary childlessness and acquiring parenthood through surrogacy. This mini review aims to examine the clinical outcomes, complications, and ethical considerations surrounding UT and compare it with surrogacy.

Introduction

Absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI) refers to infertility caused by the absence or abnormality of the uterus, which prevents embryo implantation or the maintenance of pregnancy (1,2). Uterus transplantation (UT) has emerged as a potential treatment for AUFI that has been successfully conducted in over 10 countries. However, alternatives like surrogacy are available for AUFI. The UT procedure involves transplanting a uterus from either a living donor (LD) or a deceased donor (DD) into a woman with AUFI. According to the Third International Congress of the International Society of Uterus Transplantation, a total of 91 UT procedures has been performed globally, with 71 from living donors and 25 from deceased donors, resulting in 49 live births, 40 from LD UT and 9 from DD UT (3-7). Technically, UT is a complex and multi-step surgical procedure. It requires lengthy surgeries, significant psychological and emotional challenges for both donors and recipients, ongoing immunosuppression and potential in utero effects on offspring with substantial costs. Women undergoing UT must be carefully screened, be in a supportive relationship, and fully understand the risks and benefits of the procedure. As such, concerns regarding the physical and psychological complications for donors, recipients, and neonates have been raised (8). This manuscript aims to provide an overview of uterine transplantation and comparisons with alternative methods like surrogacy, emphasizing gaps in the literature regarding recipient challenges and ethical considerations that are often overlooked in previous studies.

Surrogacy versus UT

UT has been the topic of intense ethical discussions which are related to the non-life saving experimental nature of UT, the existence of successful alternatives (such as surrogacy), and the risks for the donor. It has been argued that UT improves on other options, such as surrogacy, only by satisfying personal desire to experience gestation as well as childbirth and that these are insufficient to justify the high financial cost associated with UT. These criticisms have also been specifically deployed against public funding for UT in countries with socialized medical care and insurance-based or mixed systems (9,10). Caplan et al. pointed out the different risk-benefit ratio involved in a transplant procedure not meant to be lifesaving but instead meant to be quality-of-life improving and warned about the risk of “therapeutic misconception” for a procedure that is experimental (11). In addition, Arora and Blake, who justified UT for its non-life saving nature and believed that alternatives are available, nonetheless, also invoked patients’ autonomy in choosing between alternatives, stressing the importance of informed consent and the fact that UT is experimental (12). Dickens et al. discussed the ethics of uterus donation and the familial or social pressure that a related donor may feel or the motivation of an unrelated donor (13). Accordingly, it is better to state that UT is associated with considerable risk and currently necessitates conception via in vitro fertilization (IVF), a highly medicalized pregnancy and delivery by Caesarean section. Additionally, there is limited availability for this procedure as it is offered at few specialized centres globally. When comparing the risks of surrogacy with those of the woman undergoing UT, the former could be opted because the latter one needs to tolerate at least three surgical procedures and take immunosuppressive medication to be able to have a child. This imbalance has no solution when only the clinical aspects of the comparison are considered. The ethics for UT are complex. The question remains whether it is ethical to put two people at risk when performing a UT when other options are available (14,15). In contrast, according to the National Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance System data from 2020, gestational surrogacy is currently offered by 90% of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention-reporting IVF centres in the United States (16). It is beneficial for patients with serious medical diseases, such as heart or kidney patients, prohibited from becoming pregnant, and repeated implantation failure in assisted fertilization (17). Some women cannot bear the burden of pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, as well as disability due to old age and the fear of passing on debilitating genes (18). There is a genetic link to the child when the embryo(s) originate from the gametes of the intended parents. In addition, it has a lower medical risk than the UT procedure. Besides, more control over prenatal care and embryo selection by IVF would be achieved. Legislation on surrogacy varies between countries and it is legally accepted in several countries (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Russia, Israel, Iran, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Georgia, Greece, Brazil, South Africa and India) (19,20). Some studies cited that UT transplantation presents unique advantages in specific contexts. The most important benefit of UT is that it allows women with AUFI to personally experience pregnancy, gestation, and childbirth, which can have profound psychological, emotional, and social value (9–12). Furthermore, in countries where surrogacy is legally restricted, culturally unacceptable, or ethically controversial, UT may represent the only available pathway to achieve biological parenthood (19–21). In these cases, UT not only preserves the genetic link between parents and offspring but also respects the autonomy of women who wish to undergo the process of gestation themselves. Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that surrogacy remains the safer option overall, given the high surgical risks, complications, and need for lifelong immunosuppression associated with UT (22).

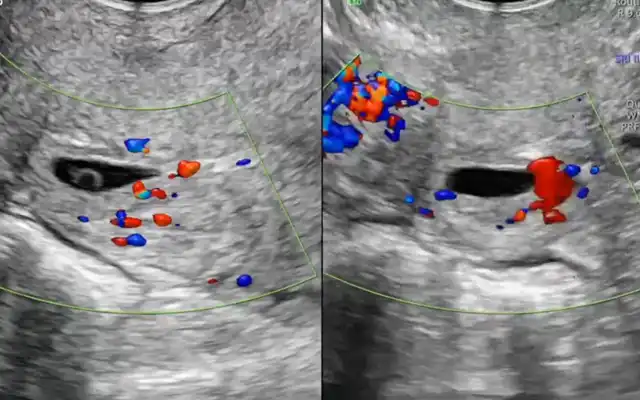

UT Challenges related to recipients

The ethical implications of UT as an alternative to surrogacy remain contested, particularly regarding the role of genetic continuity. Surrogacy preserves a genetic link between intended parents and offspring, framing UT as an ethically superior option based solely on genetic considerations would be premature, given the procedure’s experimental nature, the transient use of the transplanted organ, and unresolved questions about long-term risks. The debate must also account for cultural and legal disparities in how societies weigh genetic parenthood against gestational experience. Until further evidence clarifies these trade-offs, ethical evaluations of UT should remain provisional and context-dependent challenges related to recipients (23-26). Also, for the woman who undergoes a living donor uterine transplantation (LDUT), the risks of the operations, the LDUT itself, the Caesarean section to deliver the baby and the hysterectomy after the delivery are problematic. As UT is considered as a vascular composite allograft (VCA), these ethical concerns have been discussed among members and societies of the transplant community. In addition, Perier et al. reported several complications in UT recipients, including vaginal stenosis (71.4%), infections (44.4%), cytopenia (57.1%), and renal toxicity (14.3%) (27). Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is a common concern in UT recipients, particularly when tacrolimus is used as part of the immunosuppressive regimen (28). There was a significant reduction in GFR from pre-transplant levels (106.4 mL/min per 1.73 m²) to post-transplant follow-up values (92.1 mL/min per 1.73 m², p = 0.001). The graft failure rate is 26%, with 72.7% of failures attributed to anastomotic issues and thrombosis, and the remainder due to haemorrhagic shock, infection, or chronic rejection (29- 31). Kisu et al. reported an overall graft failure rate of 19.8%, with a higher rate in DD UT (28%) compared to LD UT (16.9%) (6). The chronic exposure to immunosuppression in UT recipients is associated with a decline in renal function, which can persist even into the postpartum period (32). Veroux et al. noted that 18.6% of LDUT grafts were lost, with the most common causes being vascular thrombosis, recurrent infections, venous outflow obstruction, and poor reperfusion after vascular declamping (33). Given that most uterine living donors are postmenopausal, studies indicate that the size of the uterus decreases with age and that atherosclerosis may reduce uterine vasculature, increasing the risk of graft failure due to poor reperfusion or thrombosis (34). Furthermore, UT recipients may face increased infection risks during pregnancy due to the physiological immunomodulation associated with immunosuppressive therapy. In some cases, graft removal has been necessitated by infections, including uterine abscess, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and candida as well as septic abortion caused by escherichia coli ((29,35,36,37). Recipients must be fully informed about the possibility of graft removal before or during pregnancy due to medical or surgical complications, which could lead to ethical and emotional dilemmas regarding the termination of a pregnancy (38). Ayoubi et al. found that 32.3% of UT recipients experienced complications classified as ≥ Grade III according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, with 23.5% of these complications resulting in graft removal (39). Vaginal stenosis, a frequent complication, often requires re-intervention or stenting (35,37). While some studies have suggested that pre-transplant vaginal characteristics do not influence the incidence of vaginal stenosis, the condition itself does not appear to hinder conception of pregnancy (37). There is currently no early biological or radiological marker to assess uterine function post-transplant. Evaluation typically involves Doppler ultrasound monitoring of uterine arteries, uterine size, and endometrial growth, along with regular monitoring of menstrual cycles. Transplant success rates have been reported to be 74% overall, with 75.0% success in LD UT and 57.1% in DD UT. Pereira et al. cited that pregnancy rates in recipients with viable grafts were 70.3% overall, with 84.6% of pregnancies resulting from LD UT and 15.4% from DD UT. The live birth rate per pregnancy was 60.7%, with 73.0% from LD UT and 27.0% from DD UT. However, 34.6% of recipients experienced at least one pregnancy loss (27). Obstetric complications, including gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, preterm labor, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and placentation abnormalities, have been reported (30,37,40). Preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and hypertension remain common complications in UT recipients (15.4% each), and the correlation between these complications and transplant status is still under investigation. Screening for gestational diabetes is particularly important due to the immunosuppressive therapies involved. Organ transplant remains an invasive procedure with significant risks related to the surgery itself, to rejection and immunosuppression, therefore each expansion of transplantation medicine (beyond life-saving transplants) challenges the ethical balance (41).

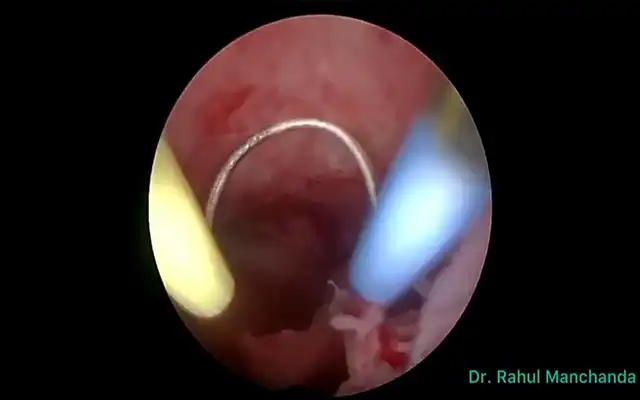

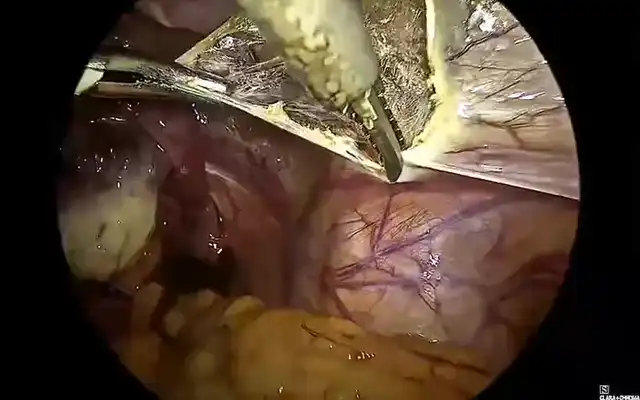

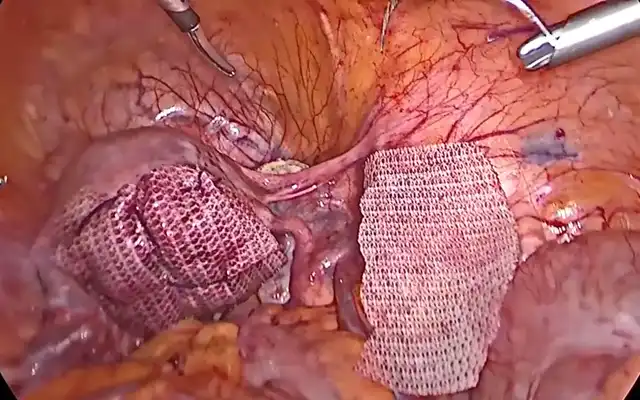

UT Challenges Related to Donors

Hysterectomies performed on living donors generally take around 10 hours due to the complexity of the venous system surrounding the uterus, whereas surgeries involving deceased donors typically last up to 3 hours (29). Once the uterus is confirmed to be healthy, implantation surgeries are usually conducted via open surgery, lasting between 4 and 6 hours (42). Brannstrom et al. reported that the duration of open procedures was between 2–6 hours in 73% of cases (29).

UT Challenges Related to Neonates

Approximately 60.7% of neonates born from UT recipients were preterm, while 39.3% were full-term (30,37,40). Neonatal complications, such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), neutrophilia, and hypoglycaemia, have been observed. Furthermore, foetuses may be exposed to immunosuppressive treatments administered to their mothers, potentially affecting fetal development (43). Prematurity and low birth weight are common, likely due to the transplanted uterus’s reduced ability to grow and function compared to a native uterus. Additionally, UT recipients often do not feel fetal movements or contractions, further complicating monitoring of the pregnancy. As a result, many UT neonates require extended stays in neonatal intensive care units (NICU), primarily due to RDS (2).

Ethical Considerations

Uterus transplantation is classified as a non-vital organ transplant, raising ethical concerns regarding its necessity and risks (44). Gestational surrogacy could be a low-risk procedure in comparison with UT requiring complicated surgeries followed by high-risk pregnancies (22). The latter must undergo at least three surgical procedures and take immunosuppressive to be able to have a baby. Ethical principles such as beneficence, non-maleficence, and autonomy are frequently discussed in the context of UT (45). Given the necessity of ongoing immunosuppressive treatment, which can have long-term health implications, most centers limit recipients to a maximum of two pregnancies (46). Informed consent is essential, ensuring that the women and their partners are fully aware of the risks involved in UT. The choice of living versus deceased donors also generates an ethical debate. Although success rates are comparable, living donors face significant health risks, which raises concerns about the ethical implications of their involvement (47,48). Age restrictions, which limit eligibility to women under 30, are common in many centres offering UT. This policy, while justified by medical and scientific considerations, may exclude women over 30, despite the increasing trend of postponing childbearing. This restriction could be seen as unfair, especially in light of the availability of alternative assisted reproductive technologies for older women (49).

Conclusion

UT is in its infancy more experience is necessary to draw definite conclusions. Although the technique does offer new possibilities for women with AUFI, yet UT remains a complex and high-risk procedure. Therefore, an alternative option such as surrogacy is available. Although both UT and surrogacy are solutions to AUFI that allow the transfer of genetic material from intended parents to a child, it is essential to consider whether the advantages of the UT outweigh the disadvantages as compared to surrogacy.