Authors / metadata

DOI: 10.36205/trocar trocar4.2021001

Abstract

This study aimed to explore the current opinion on hysterectomy choices amongst the members of International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), as well as the perceptions and potential barriers that may inhibit gynaecologists from offering a minimally invasive hysterectomy to their patients. Additionally, it aimed to evaluate the attitudes towards the modes of access of hysterectomy. Finally, it assesses the perceived contraindications to performing vaginal hysterectomy (VH) or laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH).

Introduction

Hysterectomies are the most common operative procedures for benign gynaecological diseases (1). At present, abdominal hysterectomy (AH) constitutes the most common approach, despite the fact that vaginal hysterectomy (VH) or laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) should be the preferred route. It is estimated that approximately 20% of women living in England and Wales will have undergone a hysterectomy before the age of 55. Most surgeons perform up to 80% of procedures via the abdominal route (2,3,4,) The reason for this can be explained, in part, by personal preference, but is mainly due to a lack of training and experience, thus resulting in the surgeon’s reluctance to perform VH. This is the case particularly in nulliparous woman in the presence of uterine enlargement, in women with previous surgery or women who have undergone a previous caesarean section. The above factors should not be considered as contra-indications to performing VH and there are numerous publications which support this (5,6) The rationale for LH is to convert an TAH into a laparoscopic/vaginal procedure and to thereby reduce trauma and morbidity. In the USA, one in three women is deprived of their uterus by the age of 60 years. Out of these women, 22% have undergone a vaginal hysterectomy. The introduction of LH increased the number of VH to 33% (7) however, the additional 11% were LAVH. Despite the introduction of LH, 66.1% of the hysterectomies performed in USA are abdominal. The benefits of LH are similar to those of a VH, with minimal post-operative discomfort, less need for analgesics, shorter hospital stay, and quicker return to normal daily activity. There are also fewer post-operative complications, as well as reduced hospital costs compared with (8,9,10,11) Due to the increase in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed, the authors are interested in exploring the potential provider-related obstacles to offering a minimally invasive hysterectomy to their patients. The authors would also like to evaluate provider attitudes towards mode of access and to inquire about provider perceived contraindications to perform a VH or LH.

Material method

A two-page, anonymous, electronic survey was designed in order to explore practicing gynecologist’s preferences regarding the optimal hysterectomy procedure for benign uterine conditions and the perceived barriers towards minimally invasive hysterectomy. The survey included questions on demographic characteristics, preferred approach to hysterectomy, the approximate number of surgical cases per year and potential barriers or contraindications for performing vaginal hysterectomy or laparoscopic hysterectomy. A question enquiring if surgeons have any intention of changing their approach to hysterectomy in the future was also included.

The survey was created on Survey Monkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/PFKMLRL) through an account paid for by the author. The questionnaire was designed to be brief and easy to read, so that practicing gynaecologists need not spend an excessive amount of time completing the survey. The questionnaire was validated by 12 local practicing gynaecologists who assessed the clarity and confirmed the relevance of the questions. Thereafter, the survey was amended to its present form.

The electronic survey was disseminated in the following way: a link to the survey was emailed to all practicing gynaecologists who are members of ISGE. To complete the survey, participants were asked to click on the link and thereby be directed to the survey via the Survey Monkey website. Since the completion of the survey was done online and the results were stored in bulk on the Survey Monkey server, anonymity was preserved. Moreover, no personal information was requested by the survey itself, so the identity of the participants was not revealed.

A second e-mail was sent out two weeks after the initial email to those that failed to complete the questionnaire.

Results

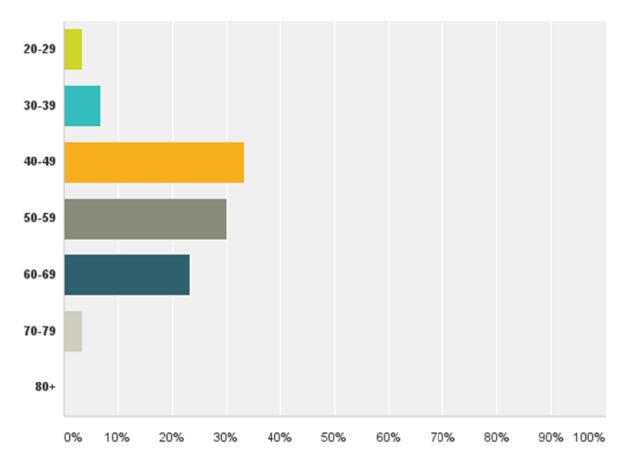

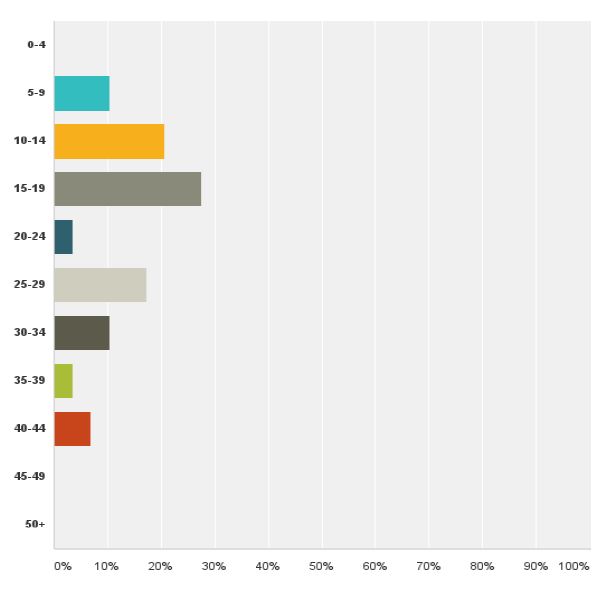

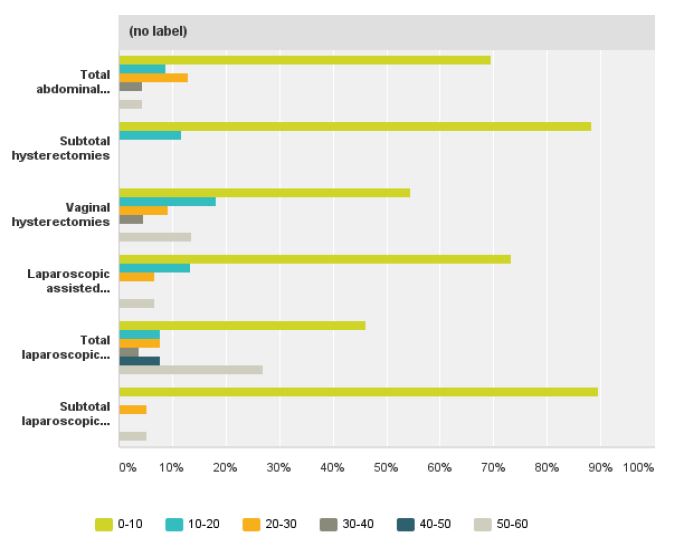

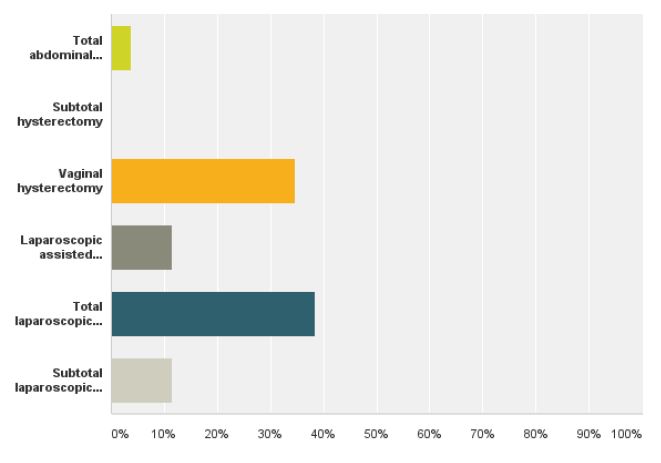

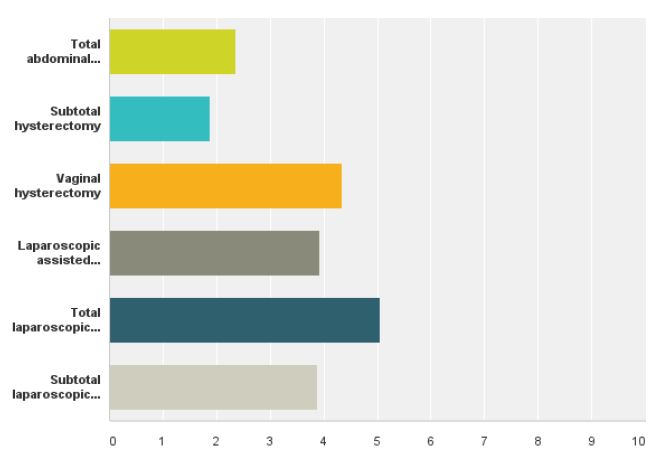

We received a response from 32 members of ISGE. Twentynine (96.6%) were between 30-70 years of age (fig 1) with more than five years in practice since completion of their registrar training (fig 2). Twenty- eight (87%) of the responders were male and four (13%) were female. The most commonly performed hysterectomy procedure that had been undertaken by the responders in the last year was TAH, 69.5%, followed by VH, 54.5% and TLH, 46.1% (fig 3). When asked about the preferred route of hysterectomy for themselves or their spouse, 38.4% chose TLH, 11.5% LAVH, 34.6% VH and 3.8% TAH as their first choice. Almost all the responders were more likely to choose a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy as opposed to TAH (fig 4).

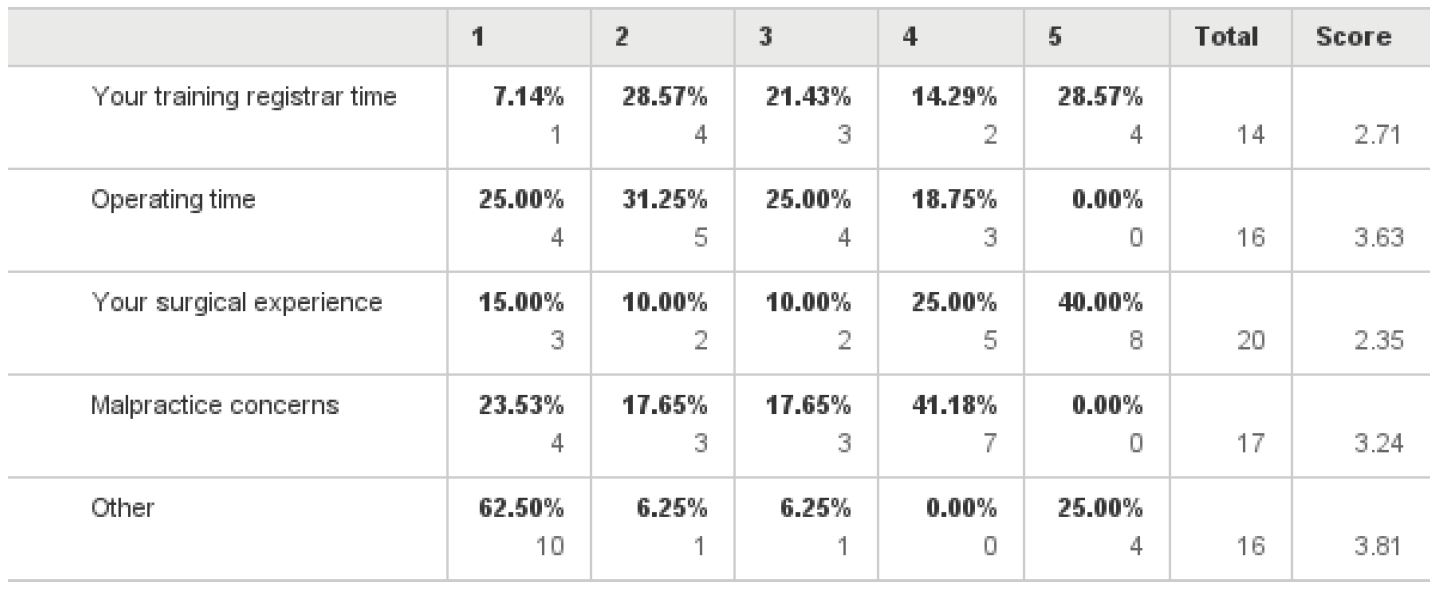

The main barriers to performing VH are listed in Table 1. Gynaecologists were asked to rank each factor on the scale of 1 to 5, with one 1 being the “least significant barrier” and 5 being the “most significant barrier”. The most significant reported barrier to performing VH was lack of surgical experience (40%), followed by lack of training during registrar time (28.5%) and then by malpractice concerns and length of operating time.

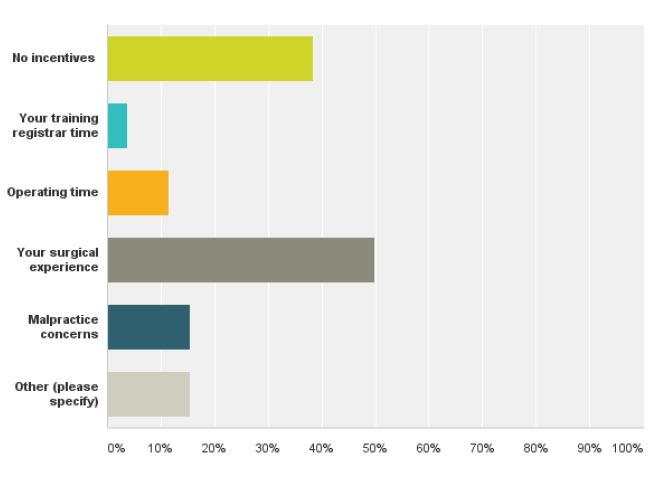

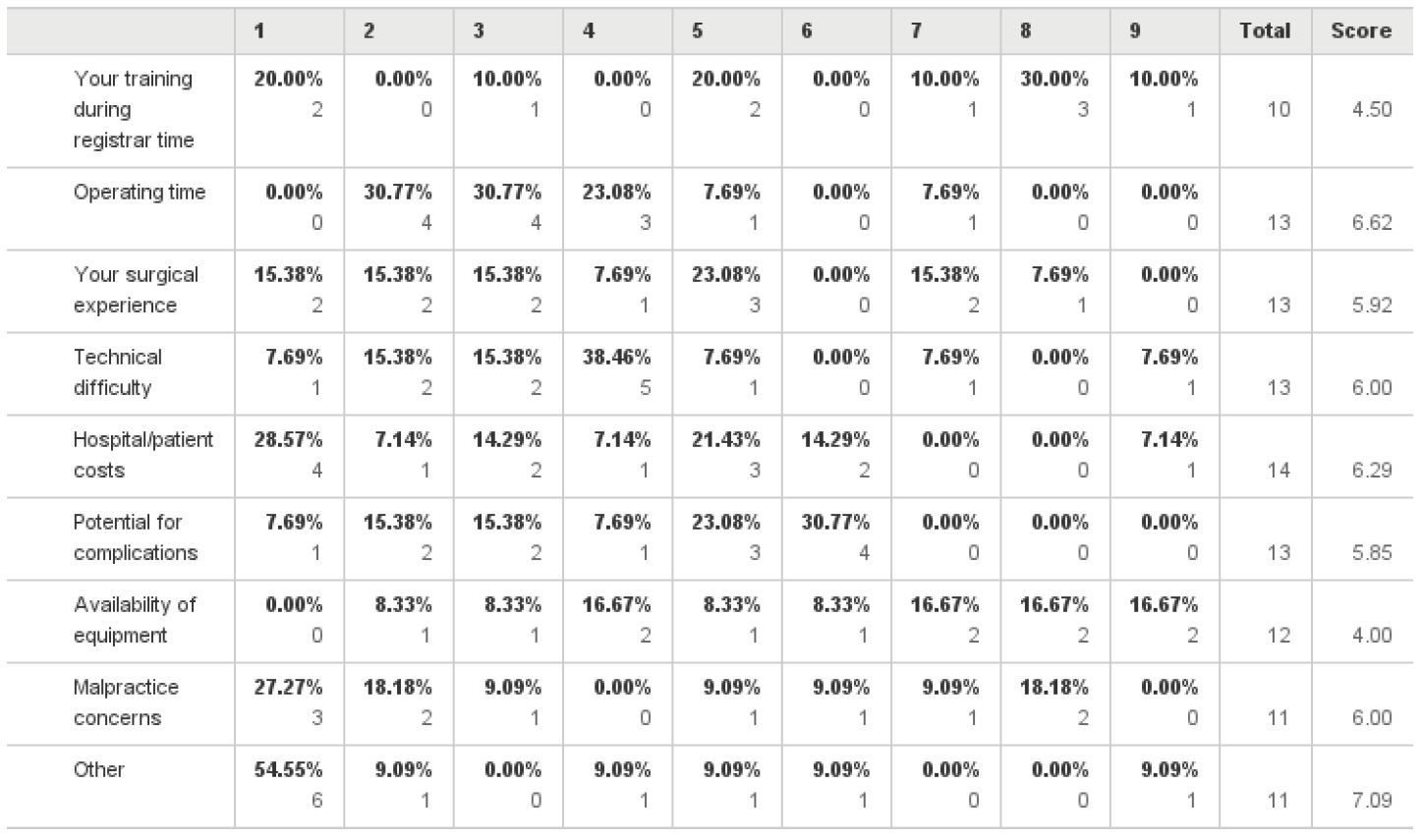

Although 38.5% of the responders did not report having any incentive to perform TLH as opposed to TAH, 50% of the responders stated that surgical experience was the main obstacle to performing TLH (fig 5). The main barriers to performing a LH are listed in Table 2. Gynaecologists were asked to rank each factor on the scale of 1 to 5, with one 1 being the “least significant barrier” and 5 being the “most significant barrier”. The most significant reported barriers were surgical experience and potential for complications with 23% respectively, inadequate training during registrar time with 20%, followed by operating time and malpractice concerns.

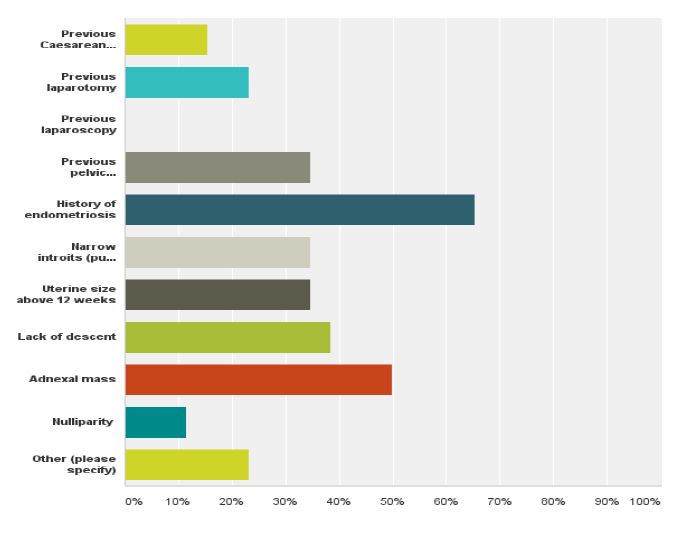

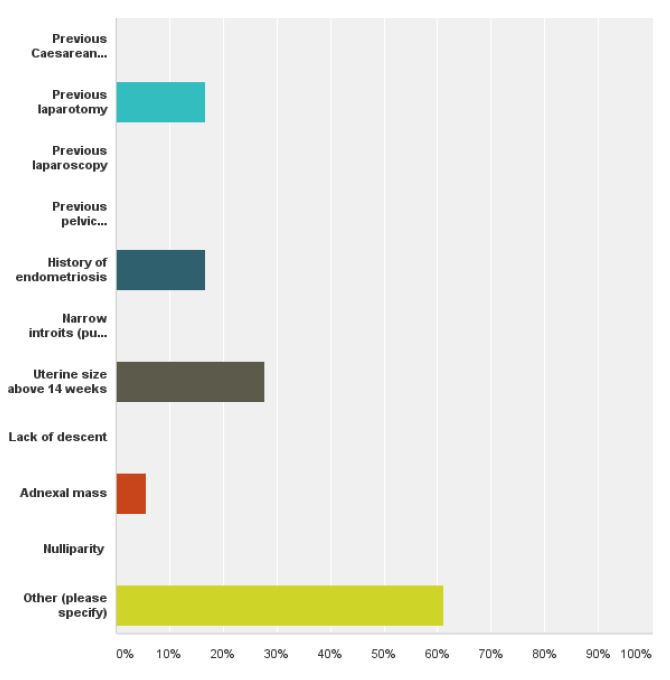

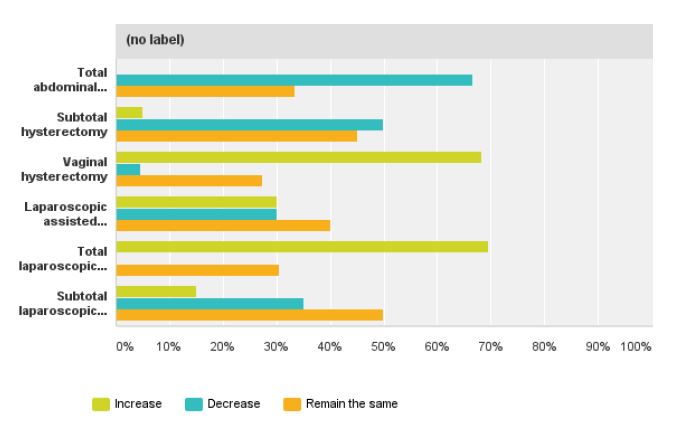

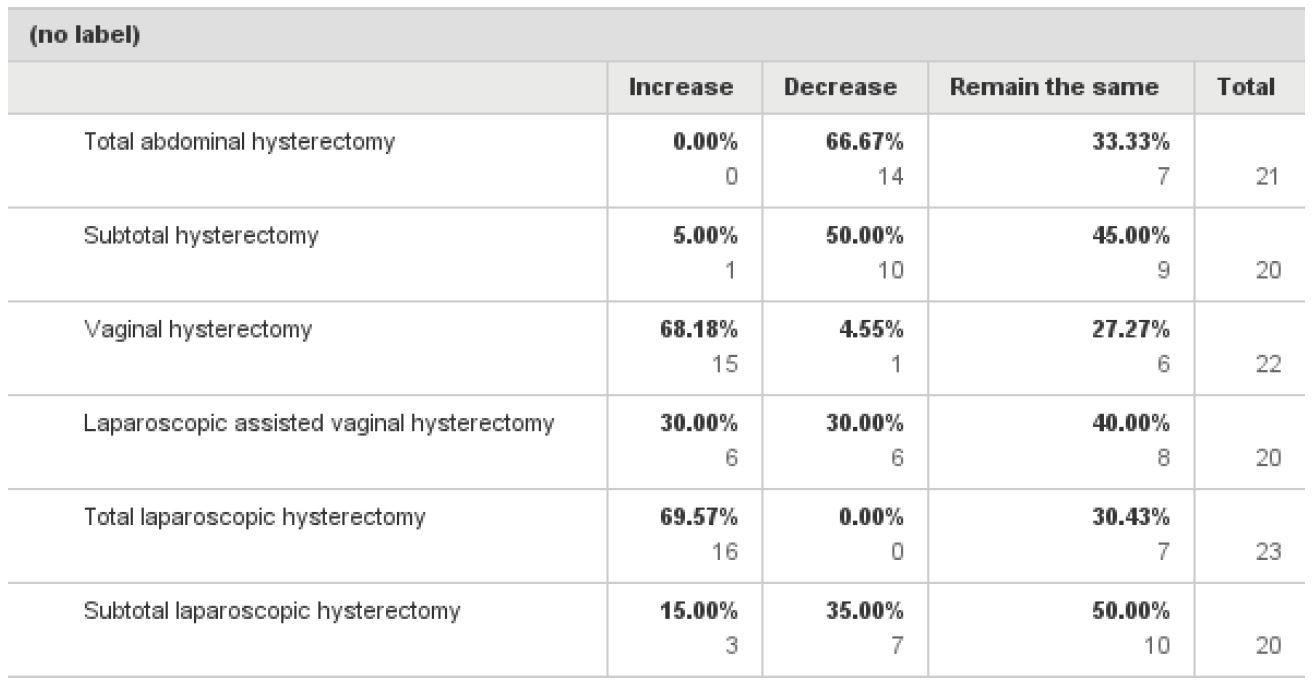

When asked about their ideal mode of access when performing hysterectomy 47% responders answered TLH, 35% VH, 13.3% LAVH and only 5% chose TAH as the ideal method of removing the uterus (fig 6). The most significant contraindication for performing VH was a history of endometriosis followed by previous pelvic inflammatory disease, narrow introitus, uterus larger than 12 weeks, adnexal mass and minimal uterine descent (fig 7). The most significant contraindication to performing a LH was uterine size, 27.7%, followed by previous laparotomy or endometriosis with 16.6% respectively (fig 8). The majority of the responders (66%) said they would like to decrease their TAH rates, 68.1% said they would like to increase their VH rates and 69.5% would like to increase their TLH rates while keeping the same number of LAVH (table 3).

Discussion

Although the number of responds from society members was disappointing, The authors found some discrepancies between practice patterns and physician preference. When laparoscopic gynaecologists were asked to rank which hysterectomy approach they would prefer for themselves or their spouse, 38.4% answered TLH with only 3.8% preferring TAH. However, the reality in their practice is different, as TAH still makes up a large majority of hysterectomies performed over one year period. TAH accounts for 69.5% of the hysterectomies performed by the responders over a period of one year. Our results are in agreement with Einarsson et al (12) in a survey performed in the United States of America (USA) among practicing gynaecologists. The results of the survey showed that only 8% of the gynaecologists would choose TAH as the preferred hysterectomy approach for themselves or their spouse. In spite of their preferences, TAH continues to be the most common hysterectomy method in the USA.

This difference between preferences and practice could present an ethical dilemma for the gynaecologists if they are not able to offer potentially appropriate candidates the hysterectomy they would recommend for themselves or their spouse. This seems consistent with the findings of this study as the participants expressed a strong desire to increase minimally invasive hysterectomies in their practice. They expressed almost similar desires to increase their rates in TLH as well in VH.

In table 3, we present the desired mode of access for hysterectomy. Identifying ways to promote the least invasive approach to hysterectomy could decrease health care costs and improve patient quality of life. The fall in VH may well reflect a switch to laparoscopic procedures but mainly, as indicated by the results of this survey, seems to be due to a lack of training during registrar time. For the last twenty five years, driven by industry and fascination of new technology, laparoscopic societies have tried to promote TLH without any obvious impact on TAH numbers. It is time to realize that laparoscopic societies need to find ways to promote not only TLH but also VH if they really want to decrease TAH numbers.

In table 1 the main barriers to performing VH are presented. When laparoscopic gynaecologists were asked to rank the contraindications to performing VH they mentioned amongst others, patients with fibroid uteri, patients with previous caesarean sections, nulliparous patients and patient with previous laparotomies. Considering the contraindications to performing VH mentioned by the responders, one can draw the conclusion that in the absence of uterine descent or prolapse, all hysterectomies are done either laparoscopically or abdominally. The obvious lack of training during registrar time may lead to a newer generation of specialists reluctant to perform VH in the absence of uterine prolapse, or performing TLH in patients who may have otherwise undergone an uncomplicated VH. The contraindications to VH, mentioned above, should not be an obstacle to remove the uterus vaginally, provided the uterine size does not exceed 14 weeks, the pathology is confined to the uterus and there is adequate vaginal access. Many studies have shown that challenging these contraindications can lead to an increase in numbers of VH. (4,5,6)

Half of the responders stated that surgical experience is the main obstacle to performing TLH, although it is an accepted and widely preferred method. The most significant reported barriers to performing TLH were mainly lack of surgical experience and inadequate training, followed by the risk of complications resulting in malpractice claims. The operating time was also of concern. Regarding TLH, the results of this survey are in agreement with a survey by Einarsson et al (13) among senior obstetrics and gynaecology residents, which shows that residents are unable to attain proficiency in most advanced laparoscopic procedures during their residency. 67% of senior residents thought emphasis on laparoscopic surgery should be greatly increased and 87% of them considered that training received in laparoscopy was important for building a successful practice.

Chen et al (14) in a survey performed in Canada found that 93% of the responders selected the endoscopic approach as their preferred approach, however, 38.7% of these responders did not feel that they had adequate training during residency to perform endoscopy in general.

The fact that the majority of the responders in this survey would like to increase their ability to offer VH or TLH approaches to their patients suggest that, if more opportunities for VH and TLH exposure and training were available, interested gynaecologist could potentially become comfortable offering these options to their patients.

This study has strengths and limitations. Firstly, it was a survey that took place amongst gynaecologist with experience in minimally invasive surgery and not general gynaecologists as in the majority of surveys published in the literature (12,13,14). Secondly, it is the first international survey, amongst members of an Endoscopic society, to evaluate barriers to performing minimally invasive hysterectomies. The study was limited by the very low response rate. This is something common to professional surveys. It is possible that the responders may not be representative of the overall population of minimally invasive gynaecologic surgeons in practice, which will affect our results.

Conclusion

For the members of the ISGE, their preferences for access to hysterectomy compared to their actual practice appear inconsistent. This suggests that strategies should be initiated to increase training opportunities in minimally invasive hysterectomies, especially VH. Guidelines for performing minimally invasive hysterectomies should be put in place to help our colleagues to perform more minimally invasive hysterectomies.

References

Fig. 1 Age distribution amongst the responders

Fig. 2. Years in practice since completion of registrar training

Fig. 3. Hysterectomies performed via various routes of access by the responders in one year

Fig. 4. Method of hysterectomy preferred to be performed for themselves or their spouse

Fig. 5. Incentives and reasons not to performed TLH

Fig. 6. The ideal mode of access when performing a hysterectomy

Fig. 7. The frequency of contraindication to performing VH, as perceived by the responders

Fig. 8. The frequency of contraindications to performing laparoscopic hysterectomy

Fig. 9. The expressed desire to change the mode of access when performing a hysterectomy

Table 1. The most significant Barriers of performing VH

Table 2. The most significant barriers to performing LH

Table 3. Desired change of the route of hysterectomy